Table of Contents

Milestone Retrospective Review: Ter Shibboleth: Drake Redux (2020) by Orl

- Ter Shibboleth: Drake Redux in the Quaddicted map archive

It’s been years since my last review, of Arcane Dimensions in 2018, and since then a great deal has happened in Quake mapping. Record numbers of new maps have been released, including many more Arcane Dimensions maps as well as a number of striking new design directions. This is the first in an intended series of Milestone Retrospective reviews, which will focus on major episode or other large content releases for single player Quake. The goal is to offer an overview and assessment of the project’s overall concept and design, to interview mappers, and summarize the contribution that such milestones have made to Quake’s rapidly expanding universe.

Ter Shibboleth: Drake Redux collects the maps of Ter Shibboleth (2017) and Ter Shibboleth Part 2 (2020), with gameplay from the Drake mod, which is included. This is a mod I am familiar with, having created Drake-based episodes back when PM was still working on the mod ten years ago. In that pre-Arcane Dimensions era, Drake was one of several aspiring comprehensive mods; earlier there had been Quoth, and there was the RemakeQuake project at around the same time, yet none of them was ultimately able to be fully completed and documented in the way that Arcane Dimensions (first released 2015) was able to do so successfully. Nevertheless, Orl was able to discover and implement Drake features which I didn’t know existed, resulting in a wide variety of challenges in a series of absolutely vast environments. This episode thus serves as an extensive demonstration of Drake, which wasn’t previously well-documented, but the most obvious manner in which this project has contributed to Quake mapping is in its creation of environments on a scale that previously would have been unimaginable. Moreover, each level brings its own all-new texture set and theme, which is the reason for the title Ter Shibboleth, i.e. Distinct Territories (compare to Terra Incognita, i.e. Unknown Territory). Each level has its own challenges, including puzzles and tough battles over the course of long routes; it should be noted that there are significant gameplay differences between Easy and Normal Skill, on Easy puzzles are simpler, routes are shorter, and bosses are fewer. Quake is no longer various flavours of mid-sized castle, where maps like Moonlight Assault (1999) were once large in comparison to the game’s original maps like Gloom Keep; some of these maps could probably fit 50 Moonlight Assaults in them. It’s an unbelievable technical achievement both for the mapper and for EricW who is thanked in the readme for his compiler tools to make this scale possible. It’s like whole a different game.

Review Part 1: Needlehorn and Blastocyst

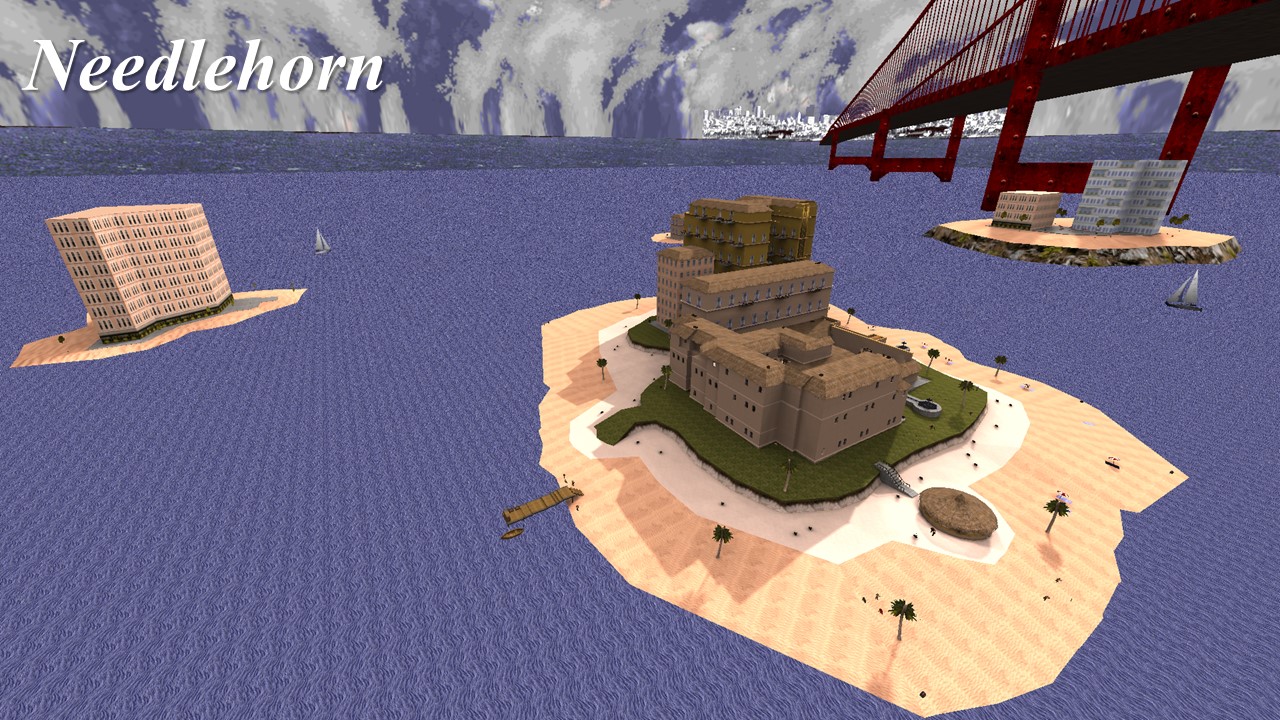

The first map, Needlehorn, takes place on a sunny island with a huge bridge in the background, as well as sailboats and even planes flying by in the distance. Another thing that makes this project unique is that every map introduces its own distinct location type, theme and texture set. If this is another game, in my experience the closest to this map (out of the relatively few games I’ve played) would be Far Cry, but the bright realist aesthetic also reminded me of Duke Nukem 3d. It’s a strange experience running around a beachfront café and hotel mowing down goblins and ogres, but while this map is indeed a far cry from Quake’s traditional gothic aesthetic, I thought it was a blast. It’s a good first map because it’s probably the easiest one to navigate, and while later maps are even larger you get some epic views from balconies and rooftops. I am certainly rusty but overall I found all of these maps quite difficult even on Normal Skill, but this map is also among the best balanced and introduces the gameplay that characterizes the episode: a relatively low monster count for the map size, but with enemy placement and Drake monsters, as well as relatively scarce supplies, meaning that you have to be careful and at times you can exploit monster infighting as well as get good use out of non-ammo-consuming weapons like the Chainsaw and Wand.

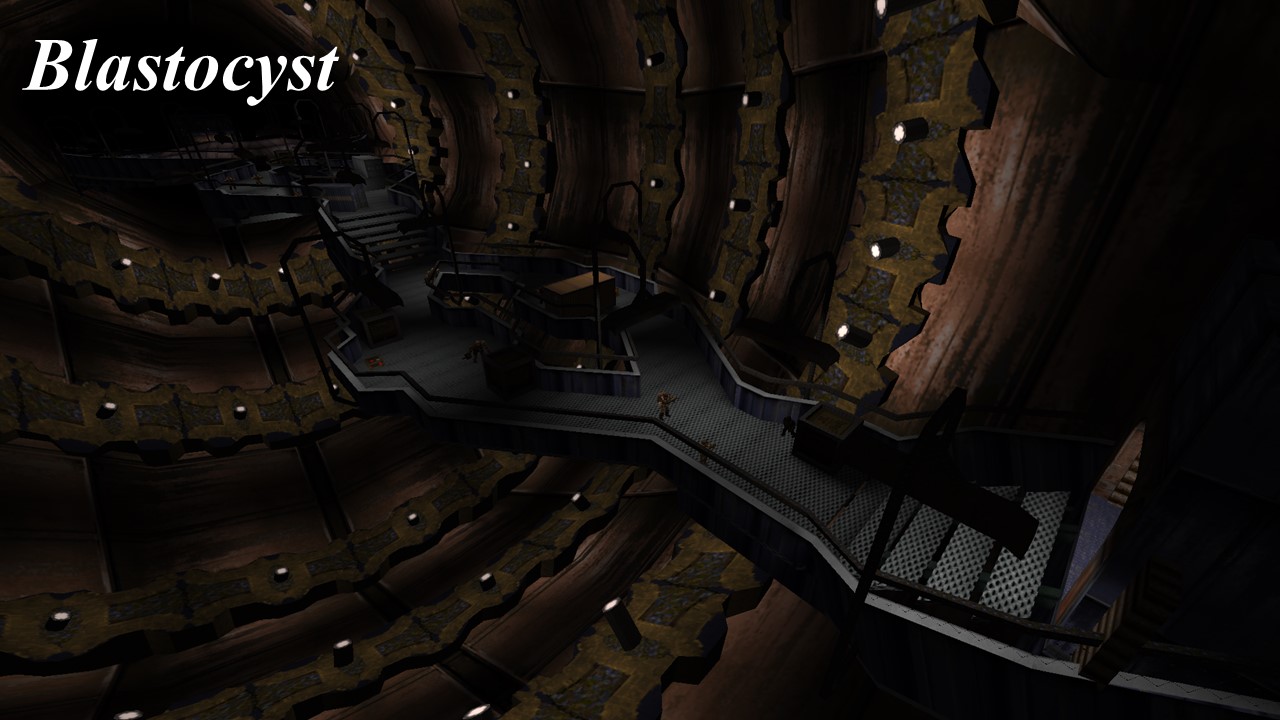

Blastocyst moves the action indoors to an industrial facility, with machinery, teleporters, lava, and base/military enemies. While I must admit that I am too dumb of a player for maps which feature significant puzzles and I do sometimes get lost if a route isn’t obvious, I had played the game Portal 2 several years ago and that gave me a reasonable sense of how things worked here. Previously in Quake there were maps like The Fly (1997) and The Anomaly 2: Water (2011), which experimented with sideways or upside-down map planes, a concept which also appears here. While I do think the navigation may be challenging for some players (it is simpler on easy difficulty), this Event Horizon-like map is an interesting experiment and it also introduces concepts deployed much more radically later on. While I have always preferred the ancient and medieval aesthetics in Quake to the military base ones, I think this map has some of the best texturing and lighting in the episode. The pale light on the metallic blue walls just looks great throughout the map, and the theme reminded me of Dark Ritual (2011).

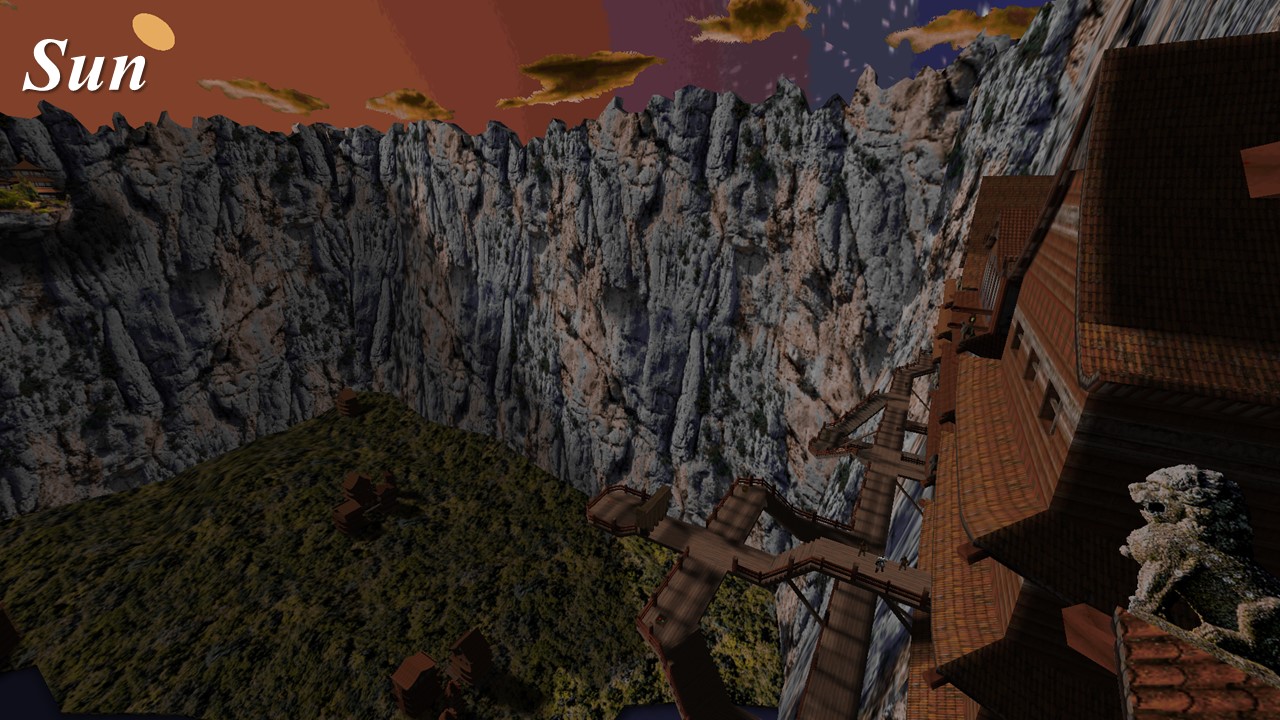

Review Part 2: Sun and Shattered Soul of the Scarab

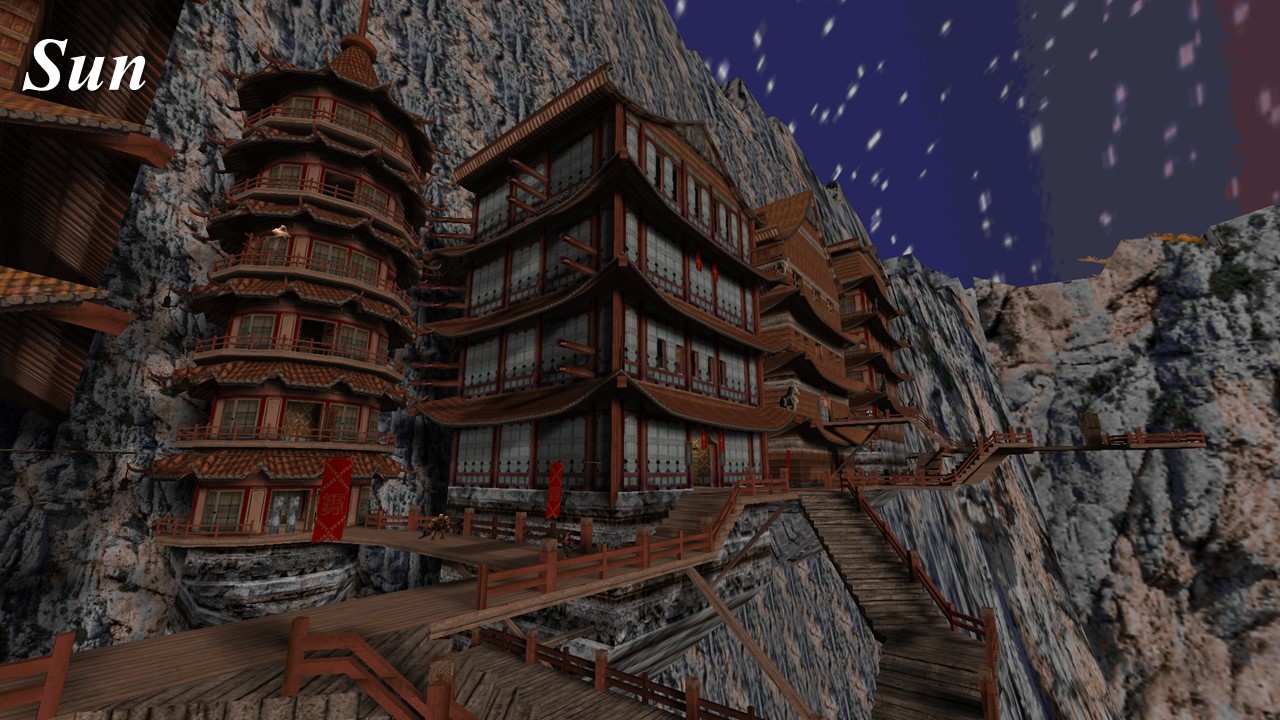

Sun has one of the coolest new environments in the episode: a Buddhist temple in Quake totally makes sense, given how maps have previously taken inspiration from Indian, Egyptian, Roman and Arabian architecture. This temple is built high up into the side of a mountain, overlooking rivers and towns below. The scale of the background scenery is vast and continues with the method of building an actual surrounding environment rather than relying on a skybox. There is another temple across the valley where distant enemies fire rockets from near the end of the map. Gameplay takes place in and around the four main buildings of the temple, interconnected by numerous wooden walkways and bridges. Drake monsters like the imps, shadow wizards, goblins, and wraths seemed very suitable for the environment here, and the ambient sound in this map was a particularly nice touch. Some of the navigation was a bit awkward (it wasn’t immediately obvious for me where to use the gold key, for example, and it’s perhaps too easy to fall off, while some areas players need to go through including staircases, are a bit cramped and gloomy and so can be hard to find). Overall, though, this is an excellent map with a fascinating new theme which reminded me of the mountain temple in Batman Begins.

It’s ironic that the map which draws on traditional Quake aesthetics the most, with a creepy Lovecraftian concept, is probably the one I enjoyed least out of this episode’s maps. It’s an absolutely massive broken, fragmented and warped “castle,” suffering the effects of some kind of dimensional rift. In every direction, fallen towers, walls, bricks and stones are scattered about chaotically, watched over by a huge eye. Much of the gameplay takes place in semi-open ramparts, halls, towers and courtyards; some are upside-down and many are connected by elevators, wind tunnels, and teleporters, and water (watch out for traps). This is a hugely ambitious map with a cool idea behind it, but I think it works better in theory than in practice to some extent. For me the main problem is that it’s not clear how the various parts of the gameplay space relate to each other, so while I was generally able to continue making progress through the map, I never had a strong sense of where the next place to go would be or how much progress I had made (other than by checking the monster count). Of course, the sense of distortion and confusion is particularly appropriate in this map, just as the sense of being lost in a hostile environment was appropriate in Warp Spasm (2007). This is an interesting and challenging experimental piece perhaps comparable to Lower Forecourt (2009) or Disjointed Realms (2018), but it’s a good thing that players will only encounter it after getting used to the large scale and complex backtracking in previous maps.

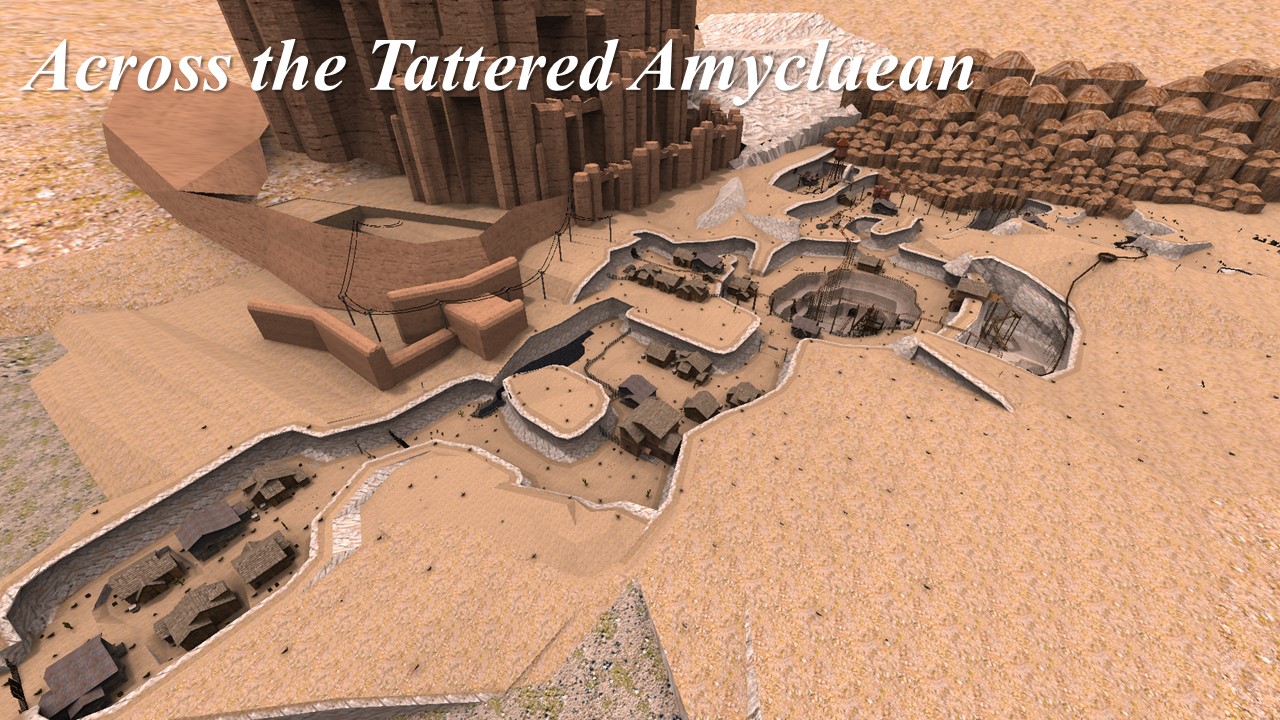

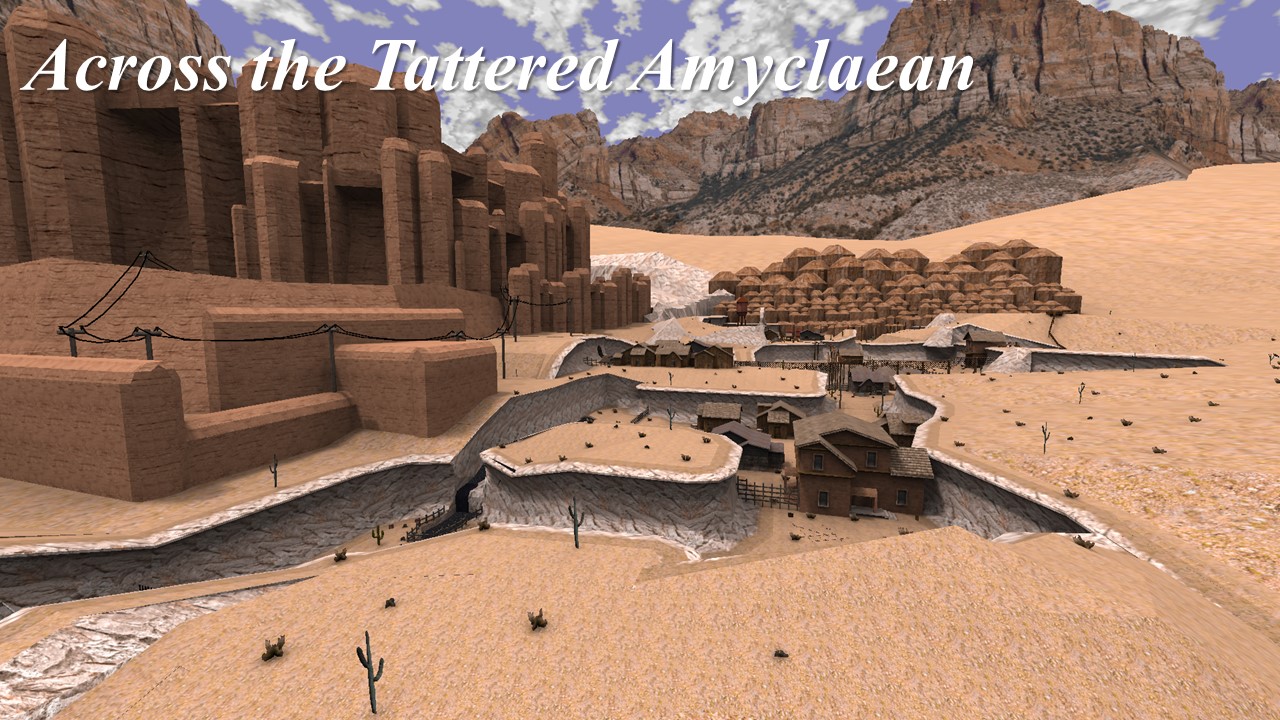

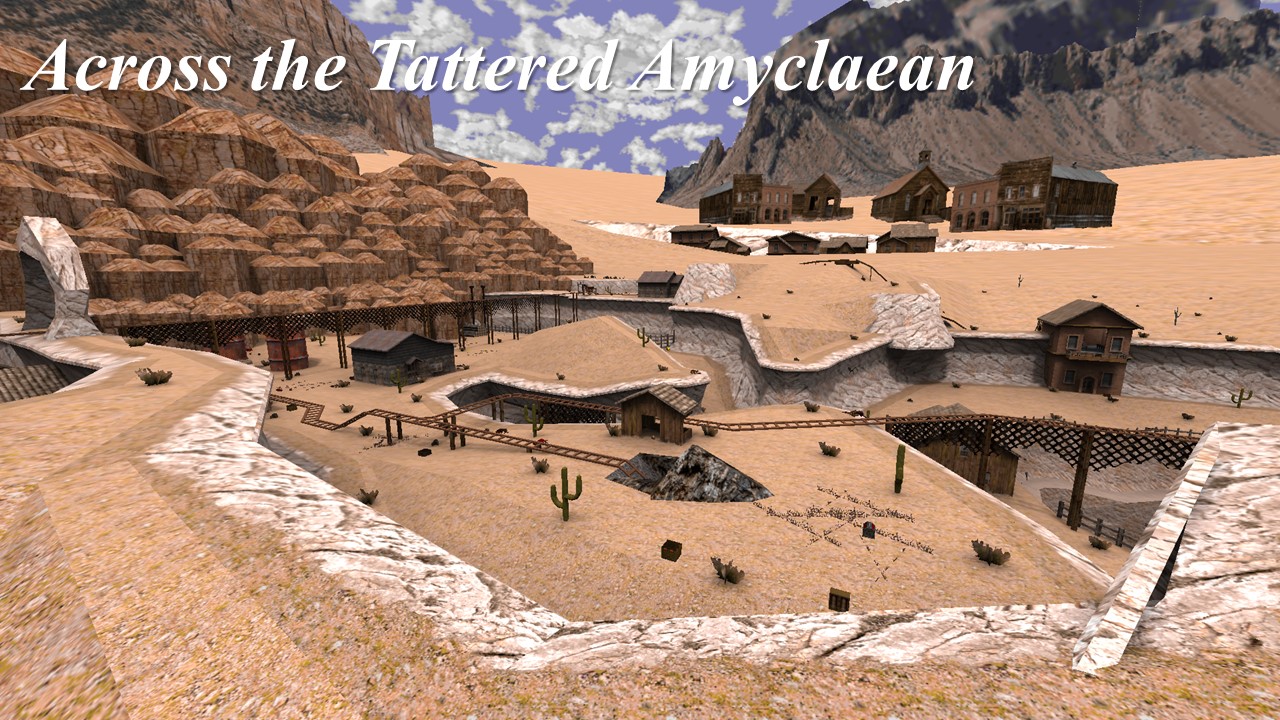

Review Part 3: Across the Tattered Amyclaean and Galiduse Point

This huge open map takes place in an old mining town, situated in the foothills of an arid mountain range. Cactuses dot the desert and old wooden buildings and rusty equipment are all over the place. There had been one or two attempts at a kind of “western” theme in Quake before, such as Ghost Town (1997), but this is a quantum leap beyond any previous take on such a theme. The shanty town which forms the map’s gameplay area is kind of dug down into the desert, with a pit mine excavation at the centre, mine tunnels coming up from below, rocky foothills at the edge of town, and an old graveyard. It’s a beautiful and surprisingly “Quakey” setting (the tech enemies such as enforcers, drones, and centroids may have, like the player, invaded from another time). It’s also one of the gameplay highlights of the episode, fighting through the streets and canyons, and with great use of enemies like hell hounds, and an epic fight later on which keeps players on their toes by introducing hostile Quake rangers (fellow soldiers who spent too much time in the desert, perhaps), demon mages who fight on the player’s behalf and summon scrags to help, and a large dragon which seemed at perfectly at home in the environment, like a vast pterodactyl hovering above the town. This is one of the episode’s most atmospheric levels and also has great ambient sound including a bird of prey’s screech; all that was missing was tumbleweeds! Gameplay-wise I found it quite tough; be sure to look around to find any Tomes of Power, which will make weapons much more effective (the chaingun-like powered-up perforator and explosive double shotgun, are quite satisfying to use).

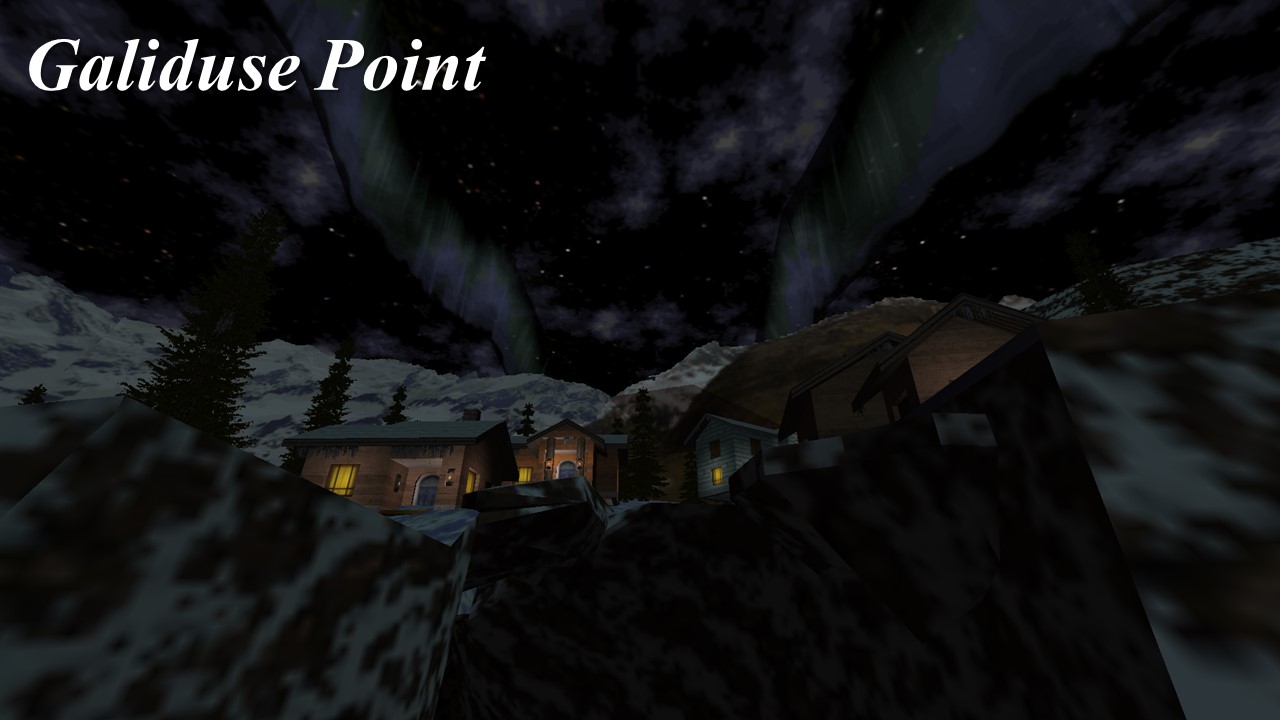

This map surpasses even the previous one in scope. Beginning in deep snowy canyons, you make your way to a village built on the side of a mountain. The village section is one of the most successful layouts in the episode, because it’s clear that progress always comes from going upward and following the road through town. It’s a very atmospheric setting with the northern lights above the snowy landscape, and the Wand, with its function of knocking back enemies and providing light, often proves useful. Snowy variants of monsters fit the environment perfectly. Near the end of the map there is a transition to a different environment, a large military bunker built into the mountain side, and guarded by a horde of grunts and even tanks. I did think this map might be better if it were split into two or even three, and possibly the themes could be more integrated like for example there could be say, five military beacons / emergency lights (maybe with some crates, vehicles and equipment) scattered throughout the village and you light each one as you pass it; this would introduce the tech concept earlier and also provide a way for players to measure progress (likewise for players in coop to tell where they have been so far).

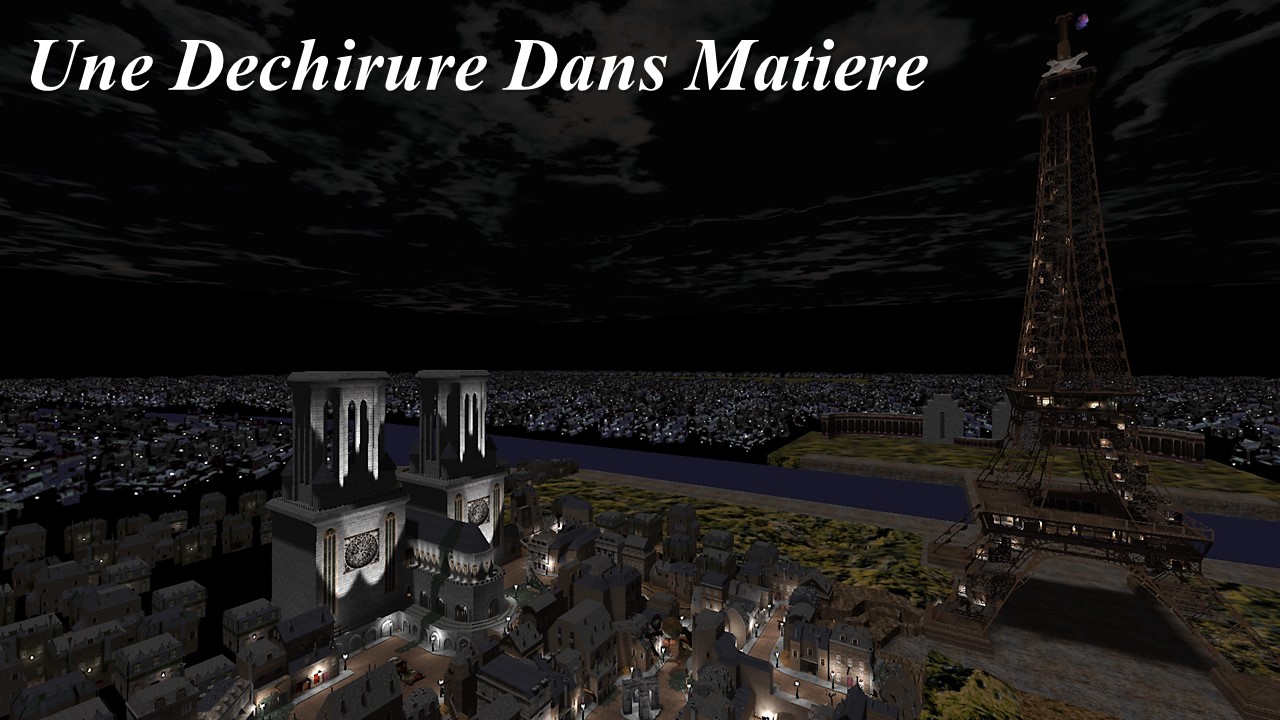

Review Part 4: Une Dechirure Dans Matiere and With Deference In Eminence

This huge and atmospheric gothic horror-themed map takes place in Paris France, in the wake of some kind of demonic apocalypse. Giant and sinister-looking bodies have jut up through the streets, hanged men swing from lamp posts, and large areas are overgrown by green spiderwebs. With ambient sound of wind, a murky palette and night time lighting, this is I think the most atmospheric level in the whole episode, it really captures a Lovecraftian, old-school horror vibe that reminded me of the classic Quake maps The Shadow Over Innsmouth (1997) and Otranto (2004), and of Doom II (1993) as well as movies like In the Mouth of Madness (1994) or Suspiria (1977). You get the sense that unbelievably awful things have happened here, and you’re just poking around afterwards hoping to stay alive long enough to get out of the city. The Drake monsters seem most at home here, especially the ones associated with sorcery/witchcraft, and I also think this map has some of the best-balanced gameplay. Navigation is quite open and non-linear, and as it’s an outdoor map and you get rooftop views at some points, it’s not too hard to find your way around, and the gameplay is challenging but not unreasonable. It’s easier to explore and find secrets, and the areas are interconnected enough that whatever order you complete the goals in, it’s clear how to get to areas you haven’t visited yet. Higher level Drake enemies like the Ice Baron and Overlord provide a challenge even in these large open areas, keeping players on their toes, and the climactic battle occurs as an epic cage match atop the Eiffel tower against a Dark Gauroch, a well-chosen and intimidating boss enemy likewise in keeping with the sinister atmosphere. There is a section on the Eiffel tower where you need to go around to the outside of the tower and make a jump across empty space to the other side of the tower, which is one of the first times in Quake that I had a sense of real vertigo. Overall, this map is a masterpiece well worth repeated plays.

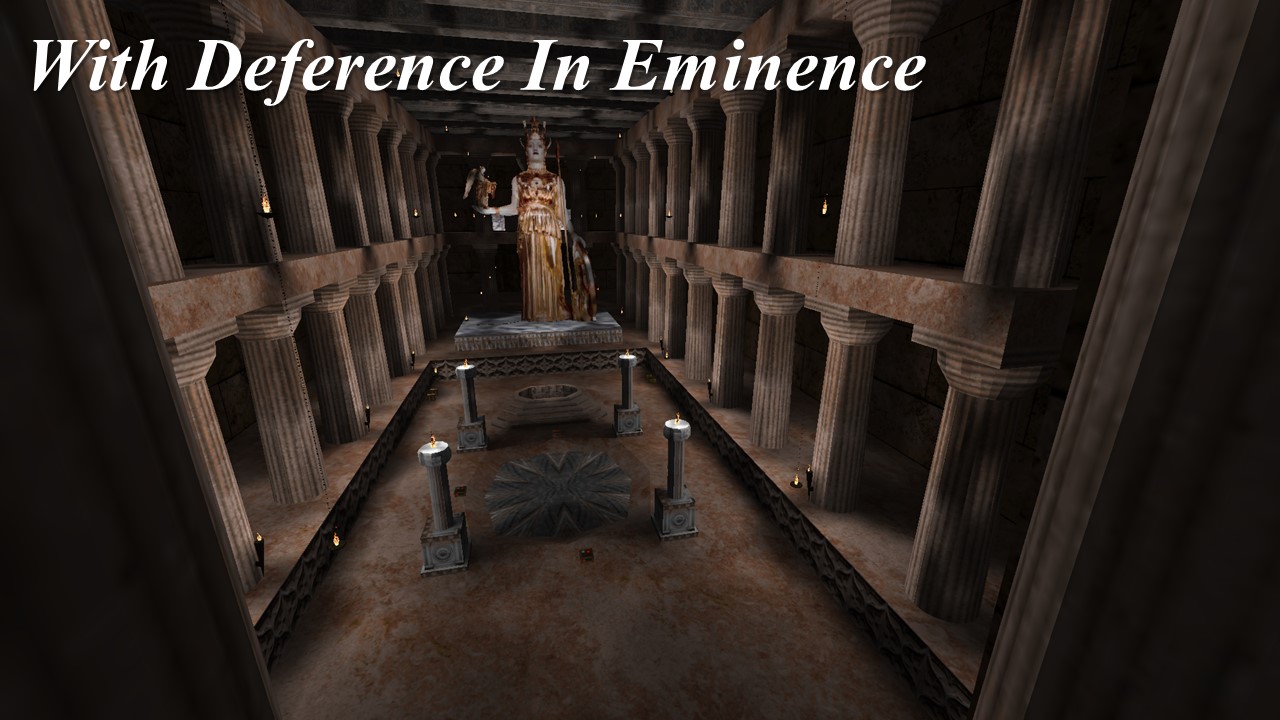

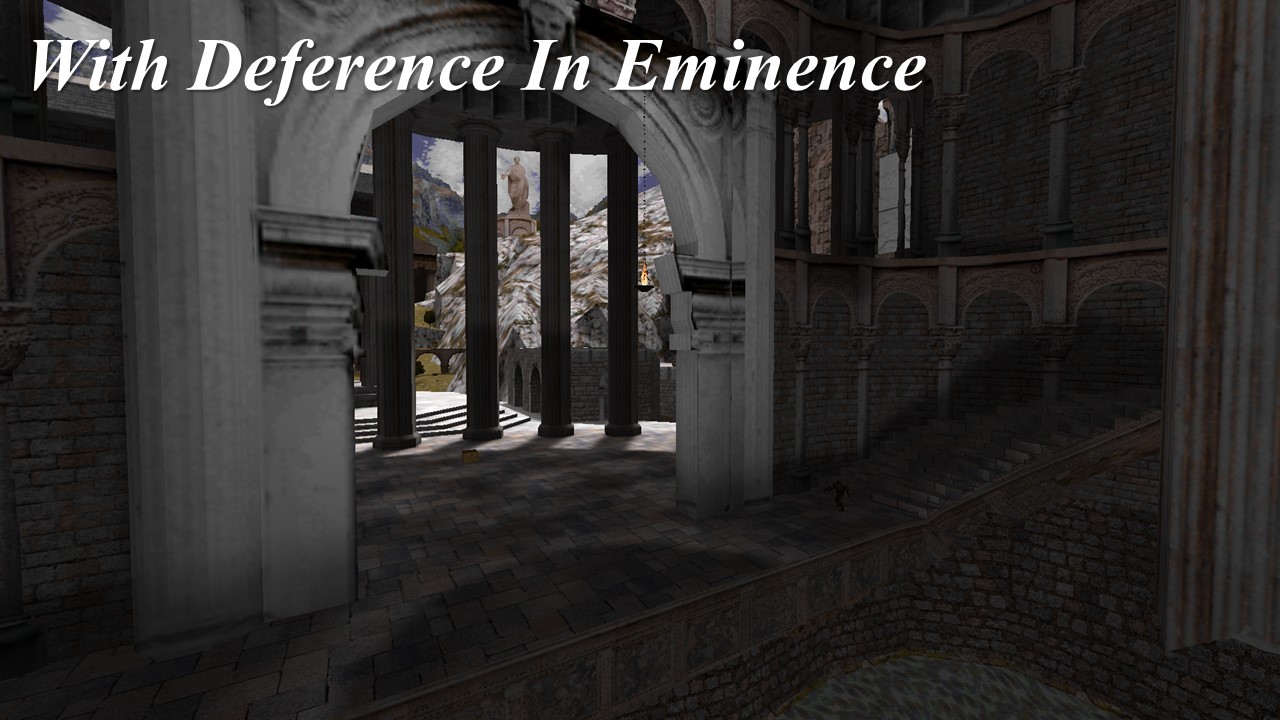

The final map in the episode is set next to and atop a vast Roman coliseum, with a huge temple complex including many buildings and aqueducts built amidst green hills, open fields and rock cliffs. The above left screenshot shows the player’s perspective from atop the coliseum, looking down on the temple complex (you reach this point by being flung by huge catapults). There is so much vertical distance that looking down on the temple complex looks like an RTS game. Indeed, if I had to compare this map to another game it might be Myth: The Fallen Lords (1997) or Chivalry: Medieval Warfare (2015). This map makes full use of Drake’s monsters and entities, including dragons and a particularly cool secret where rebel outlaws help the player fight; they are tough and fast, get right in the middle of packs of enemies quickly, which can be helpful as it’s possible to get cornered even in this vast layout as there are plenty of cliffs, walls, and building facades. The lighting is full daylight so the map is very bright and it’s easy to see where everything is and where you haven’t visited yet. This map, I think, has the best layout out of any map in the episode, every route leads back to a central hub and the map explains the routes as a quest to return four swords to four kings. Each of the routes has its own memorable moments, like running through a sunny garden dodging nail traps. One of my favourite aspects of the layout is the use of water; the temple complex has a large, interconnected aqueduct and canal system which is partly ruined, and it’s a great place to run around blowing up zombies with the grenade launcher, in classic Quake fashion. Another map highlight also involves water, when the ground gives way and drops the player into the flooded ruins of an underground temple. There is a continual sense of water erosion and water seems to be a major inspiration in this map in terms of layout, aesthetics and themes. The map concludes with a fight against probably the most dangerous boss in Drake, the Bane of the Realm, a hyper-aggressive armoured warrior with many magical attacks including creating clones of himself. Luckily the player has help from some fellow Rangers, for a suitable conclusion. This map is another masterpiece and the episode ends on an overwhelmingly strong note.

Summary

“Part of the attraction of The Lord of the Rings is, I think, due to the glimpses of a large history in the background: an attraction like that of viewing far off an unvisited island, or seeing the towers of a distant city gleaming in a sunlit mist. To go there is to destroy the magic, unless new unattainable vistas are again revealed.” -J. R. R. Tolkien

I remember that way back in Fantasy Quake (1997) one of the maps featured an inaccessible scene of a “castle in the distance.” While Fantasy Quake is memorable more as an early gameplay experiment and not for any contributions to map design, this is the earliest example I can think of in which the mapper actually built distant scenery which wasn’t at all gameplay space; previously in Quake: Scourge of Armagon and even in Doom: Knee-Deep in the Dead, maps would include windows to outdoor areas which appeared inaccessible but could often by accessed through secret passages. These maps take up this concept with a vengeance, creating levels where the scenery is so vast that even though the actual gameplay space is large, it still comprises only a fraction of the overall level’s space. When I saw the snowy village in the distance near the start of Galiduse Point, even after the previous huge maps in this episode I was still taken aback, and there you get to explore the whole vista and beyond. Usually the maps are able to establish boundaries for players by providing obvious fences and establishing rules like “a long fall will kill you” (so the bottom of a tall cliff isn’t included in gameplay space) and “most buildings are locked, so you can’t go inside.” This milestone episode is a unique experiment in vast scale, outdoor layouts, and totally new environments.

Because it is breaking new ground in many ways, it is necessary to basically invent and implement new rules, and that is where some players may find some of these maps frustrating. If I were to suggest improvements to the episode, what I would emphasize is the need for more “sign-posting.” A full start map could provide a storyline that ties these various highly distinct environments together; even something like retrieving artifacts stowed away in various specific times and places, that’s a conventional Quake story, but it could help provide through-line concept so players have a sense of where they are headed and what their goals are. Since the episode does involve various times and locations, perhaps a common “arrival” and “departure” portal, or even some kind of “pick up and drop off vehicle” could help mark the start and end of levels. I also think “shortcuts” like the mine cart in Across the Tattered Amyclaean or the catapult in With Deference In Eminence, should be used more to help players move quickly around these huge areas (perhaps a jeep or train in Galiduse Point?). The best maps in the episode, or the ones I enjoyed the most (shib1, shib3, shib5, shib6, shib7, shib8) were all able to successfully implement and communicate to players an epic journey where the place to go next is always clear, whether it’s because it’s a continual ascent up the mountainside in Galiduse Point or the quests around a central hub in With Deference In Eminence. Overall, this is an original, distinct and stunning achievement in Quake mapping, which has to in many ways invent its own rulebook (which some players may find challengingly unfamiliar), and while the scale can sometimes be so daunting that playing a single map of this episode is like playing an entire episode elsewhere, there is some excellent design and innovative gameplay here; and the last four maps in particular are masterpieces.

Review Part 5: Interview with Orl

Q: When did you first play Quake, and what aspect of the game inspired you to make Quake maps?

A: I first played Quake either around 1998 or 1999, I was still very young having only been born in 1990. I wasn’t new to video games at the time either, as I had played Doom before Quake, so when the time came to play it for the first time I sort of knew what I was getting into. A fast action first person shooter. The inspiration to create maps didn’t come around until it was first told to me through multiplayer. I had always believed that once a game is done, it’s done. There’s no adding on to it, changing it, modifying it in any way. So when I did some digging around and after a lot of troubleshooting and learning, I fired up the first custom map campaign I had ever played, which was Memento Mori for Doom II. Needless to say, I was stunned. In my mind I thought, here were levels not made by id software but instead by regular fans of the game where they could build anything they wanted. My first custom Quake campaign I played was Ikspq, and again was blown away. This only cemented my inspiration to say to myself yes, this is something I want to do; I want to create custom maps.

Q: What were your very first maps?

A: The first editor I used was Worldcraft 1.1a, and the first maps I had made were simple deathmatch maps, wherein I played against Reaper bots. If I was to create anything impressive and worth downloading, I needed to start small, as with anything. Those small, ugly maps were a crucial learning process of how Quake maps work.

Q: Looking back on your various maps, including Conflagrant Rodent (2010), Cataractnacon / Zeangala (2016), and the Ter Shibboleth project, what do you think you learned over the course of your development as a mapper?

A: Quite a lot. The most important thing I learned is I wouldn’t enjoy it as much as a career as opposed to just being a hobby in my free time. It taught me a lot about how games work, not from a programming perspective but polygons, triangles, modeling, texturing and so on. It allowed me to see and understand games in a new way. I’ve also learned what people like and don’t like in a Quake map, and I think with each release I have made I’ve gotten better, and with Ter Shibboleth being over 15 years of mapping knowledge cultivated into one big episode.

Q: What has inspired you as a mapper, particularly other maps or games?

A: Far too many to list, each map has its own inspiration from something in particular. Some Quake maps that have given me the most inspiration throughout the years are CZG’s Terra Episode, Iikka Keränen’s Ikspq Episode (1997), Kinn’s Marcher Fortress (2005), Tronyn’s Masque of the Red Death (2005), and ijed’s Warp Spasm (2007). These maps were proof that large scale levels were possible in Quake, and that was what I was aiming for. Other games that have inspired the themes and designs of my maps are: Timesplitters, Nightmare Creatures, Test Drive, Twisted Metal, Tenchu, The House of the Dead, Hydro Thunder, Jet Moto, Spyro, and Carnevil.

Q: Why the use of different themes for each map?

A: I felt custom Quake maps hadn’t explored enough different environments, it was always the same castle, base or metal structure. Occasionally you would see unique stuff like Egyptian temples or flooded swamp maps, but it was all getting rather dreary witnessing the same places over and over again. I wanted to give players something new to see, something they thought they’d never witness in Quake. The decision to make each map its own unique theme also played into this, I wanted to keep players anticipating, what will the next map look like?

Each map is a combination of both real life locations and abstract surroundings. Shib1 is a tropical island beach resort in modern times based in California, as is evident by the absurdly large Golden Gate bridge. Shib2 takes a more futuristic approach, a large underground chamber filled with traps and puzzles, where gravity can be controlled. Shib3 takes the player back in time to a far east mountain fortress based on China and Japan. Shib4 is the most classic Quake-like in terms of visuals, but reality has become discombobulated with distortions of time, gravity, and geometry. Shib5 takes the player to a mining town in the Sierra Nevada mountain range during the early 1900’s. Shib6 brings the player to present times in northern Europe, inspired by real villages in Finland and Russia, with a military bunker overlooking the quiet mountain retreat. Aurora Borealis was a big reason I chose this theme, a natural wonder of the world recreated in Quake. Shib7 is my personal favorite of the pack, it takes the player to 1940’s Paris France that has been overtaken by a dark, malevolent force. Green cobwebs cover the city streets, and large corpses emerge from the ground. Besides the demonic takeover this is probably the most realistic map based on a real location, including landmarks such as the Eiffel Tower and Notre Dame cathedral. Shib8 transports the player to southern Europe in 100 AD, where Roman and Greek architecture stand side by side and the Coliseum is the main attraction, modeled after the real thing in its present form but ten times its size.

Q: What’s your process of creating a map?

A: I first visualize what I want to make: what its theme is, major landmarks, and how it connects. As an example when creating the concept of Shib7, I visualized having the player starting through the streets surrounded by houses, with the Eiffel Tower in the distance and Notre Dame visible but not too far away, and the main plaza where most of the map interconnects. From there it's just playing it by ear, thinking about how the player will proceed between two buildings, how he will ascend the tower, etc. I think big first, then later fill in the details when the time comes.

Q: Why the Drake mod?

A: I chose the Drake mod because it was one I always remembered fondly, as well as never receiving the attention or praise other mods got like Quoth, Arcane Dimensions and Copper. Not that they don’t deserve praise, but Drake always seemed to have little recognition despite having many features that most mods do today. It was ahead of its time. While it did borrow a lot from the official mission packs, Zerstorer and Hexen 2, Drake did have its own unique tidbits like coins and gems and treasure chests which acted as health and armor boosts, much like Doom’s health and armor bonus items. Some of the other standout additions are the many different armor types with special abilities, one of which can turn the player into a dragon, the Buriza-do Kyanon crossbow and MIRV Launcher weapons, power ups like the Equalizer, Boots of levitation, Amulet of Reflection and Tome of Power and much more. In fact, a lot of the features of Drake never got to be seen in maps from before such as certain enemies and items, and I wanted to be able to showcase those in Ter Shibboleth.

Q: Finally, what inspired you to make the huge leap in map scale seen in Ter Shibboleth, and do you have any advice for other mappers who may be interested in creating (and actually finishing) Quake maps on a huge scale?

A: To create such large scale maps was something I wanted to do from the very beginning, even during the days of my first public release I had envisioned the maps I wanted to make, like a beach resort with an enormous golden gate bridge towering above, and a far east temple sitting atop a mile high cliff where you could see the forest, rivers, and other scenery down below. But I knew at the time such designs were simply not possible, both engine wise and compiler capability. My only solution was to wait until Quake engines, compilers and map editors matured enough to handle such large creations. It wasn’t until the release of J.A.C.K., the RemakeQuake project, and the very talented EricW that I could now make my visions into a reality. Probably the biggest inspiration for Ter Shibboleth’s massive map sizes is Dark Souls. While other games had huge open areas, Dark Souls was the first to make me the player feel tiny and insignificant in this land of gigantic towers, cathedrals and cities. I wanted to bring that sensation of being minuscule to the world of Quake, and I like to think that I achieved that. My advice to other mappers creating large scale maps is, don’t get dismayed. There are a small few who feel such huge levels have no place in Quake, and may even discourage you from making them. Always experiment with different ideas and themes from the norm, step away from Quake’s usual castles, tech bases and metal fortresses for something different. Even if it doesn’t turn out all that good, it will be remembered for being unique and interesting. All the tools needed to make big maps are at your disposal, and with the incredible hardware rendering capabilities of both vkquake and Spike’s FTE, processes like vis are becoming a thing of the past. Create what you want, how you want, and for whatever mod and engine you want. The possibilities really are endless.

Easily install and launch Quake maps with the cross-platform

Easily install and launch Quake maps with the cross-platform