Reverse Design: Super Mario World

Did you know you can get an eBook bundle of the entire reverse design series, including this text for less than $2? The book versions have bonus features and expanded text. You can also buy books individually.

This is the third installment in the Reverse Design series. The goal of the series has been to reverse-engineer all of the design decisions that went into classic games. Previously, we published Reverse Designs for Final Fantasy 6 and Chrono Trigger. You do not need to have read those installments to understand this one. In fact, it would be almost impossible to read this text like the other two because of how different they are. The previous two Reverse Designs have both been less than 25,000 words, and focused primarily on big-picture analysis. This kind of analysis works particularly well for RPGs—or at least it works better for RPGs than it does for platformers. That kind of analysis is also very readable; those games break down nicely into relatively short, separate sections. Even a casual reader could complete either of those Reverse Designs in just a few sittings. Reverse Design: Super Mario World is almost triple the length of either of the previous two books, and so it probably cannot be read straight through. Rather, the best way to approach this document is to read the first three sections (Introduction, Part 1, Part 2), and then use the rest of the book as a kind of guide for the level-by-level analysis that makes up the majority of the content. The ideal experience of this Reverse Design is for you, the reader, to play each level as you read its analysis.

One of the driving motivations behind this series was the notion that we might learn more about game design by studying an individual game than by studying “games” as a discipline or phenomenon. There was an article that came out during the writing of this document which I actually liked and found useful, but which illustrates this point clearly. The article included tips like "level design should be efficient" and "good level design is driven by your game’s mechanics" with general explanations of what those principles mean. I agree with both those points completely, but they're not especially helpful to anyone who hasn't already been designing levels for a long time. Although that article offers some great, bigger-picture philosophical principles on game design, it doesn't answer the questions "what do I put in this level?" or "how do I keep level 3 from being too much like level 5, while still keeping them similar?" or numerous others a designer might ask on the way towards creating a game. Our study of Super Mario World aimed to explain how Nintendo answered those questions for that game in particular; what we discovered is applicable to a great variety of games. The construction of Super Mario World reveals a pattern; following that pattern not only makes it possible to fill levels with content, but to make both those levels and the whole game coherent. This pattern exhibits three levels of ascending complexity: the challenge, the cadence, and the skill theme. Those things are defined later, because in order to understand them one must first understand Super Mario World's place in game design history. The challenge, cadence and skill theme would not be possible were it not for the development of composite games. We’re going to look at all of that briefly in this introduction, and then in depth in the sections that follow.

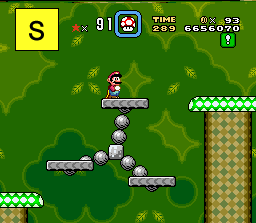

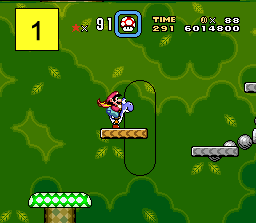

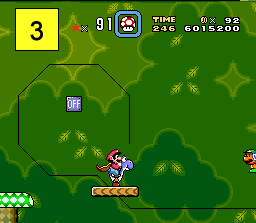

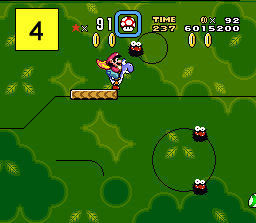

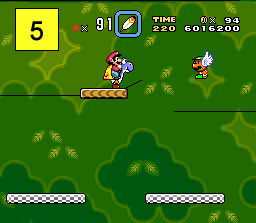

It’s probably worth giving you a look at what the things described above are, however, so that you can determine whether or not you want to keep reading this document. The level design of Donut Plains 3 illustrates each of these concepts fairly well. Below are several screenshots of various challenges in the level. WARNING: there’s a lot of jargon coming, but you don’t need to understand it yet, this is just to show where this document is going.

What you see here are, in order, the standard challenge, an evolution of the standard, an expansion of that evolution, an evolution of the first evolution, a divergent evolution, and an evolution/expansion that combines elements of two challenges. That’s not all of the challenges in the level, but that’s the important line of development. Essentially, this is a two-part level that performs a linear expansion and then linear evolution with one twist. It can be charted like this:

That sequenced analysis is what we call a cadence. Because this cadence develops a series of challenges involving moving platforms in various ways, it belongs to the platforming/timing quadrant of the composite—to the “moving targets” skill theme. That was a lot of jargon, but it should give you a good idea of where this book is going.

The first step to understanding everything that was going on in the previous paragraph is to begin at the beginning: 1981. That was the year that Shigeru Miyamoto began his career as a game designer, and introduced an idea which would shape game design immensely. Indeed, the whole reason that a survey of the design of Super Mario World is applicable to game design in general is the unique position of Nintendo, and Shigeru Miyamoto in particular. Miyamoto and his team created not just a game franchise, but a wholly new way of designing videogames. The Mario series represents the bridge from the original arcade style of videogame design to the new “composite” style of videogames, which became the dominant school of game design from 1985 until about 1998. Part I of this document, which follows this introduction, will comprehensively define what composite games are. The short version is this: composite games combine two or more genres in a specific way to achieve (and maintain) a specific form of psychological flow. Haphazardly mashing two genres together doesn’t work, but Miyamoto and his team figured out numerous techniques that would allow genres to play together in compelling ways. Game designers at different studios all around the world saw Nintendo's breakthrough and started using composite design techniques immediately, and with great success. A huge variety of games—everything from Mega-Man to Portal, from Doom to Katamari Damacy—rely heavily upon composite design ideas. Early Mario games were always on the cutting edge: virtually every Mario title between 1985 and 1996 saw an advance in the practice of composite design in a clear and meaningful way. Super Mario World is no exception, and so throughout this document there are frequent references to how the gameplay uses composite design techniques to keep the player entertained.

There is one last proviso that needs to be said here. Although we have found numerous patterns in Super Mario World and the history of game design as a whole, it is not our opinion that designers intentionally planned all of these things. In fact, Shigeru Miyamoto himself has admitted on more than one occasion that for all of his best games, he and his design team tried a huge number of different design ideas, and simply kept which ideas worked the best. Therefore, our opinion is that composite game design is merely a natural evolutionary step in the development of videogames. Composite design techniques worked well, and so designers kept using them, even if they didn't fully realize why they worked. It's likely that game designers have gradually become more conscious of the nature of composite design and composite flow, but proving this point would take a much larger study than the one being attempted here. It is enough to say that Super Mario World is a great example of the Nintendo design team taking their previous design efforts a step forward, and refining the practice of composite design in the process.