Reversing the Design: Chrono Trigger.

Hello, readers! If you're interested, you can get a high-quality ebook version of this Reverse Design, with lots of improved features. Get a preview of the RD: CT ebook here.

Also, this isn't our first Reverse Design. Check the main page for Reverse Design: Final Fantasy 6.The Two Games of Chrono Trigger

At the heart of Chrono Trigger is the question of whether or not events are inevitable. Every element in the game is used, at one point or another, to deal with this question: story, gameplay, even art and music. This doesn’t mean that the game makes the question (or its answers) obvious; indeed, Chrono Trigger is a very sly and deceptive game. Even while the game is showing players one answer in the plot, it’s giving them another answer through the gameplay. A decade before anyone was writing about “ludonarrative dissonance” the designers of Chrono Trigger had confronted the problem, worked it through, and deliberately used it as a resource. Because they expected players to simply overlook the (seemingly) inevitable disconnect between story and gameplay, the Chrono Trigger team decided they could manipulate the player through this expectation. Right up until the jaws of tragic defeat snap shut on the main character, the player expects something different. But then, as players are handed the sad answer that fate is inescapable, they get a second answer: that the tragedies of history can be averted, after all. The gameplay becomes harmonious with the plot, and we have a comedy that follows and undoes the tragedy before it. That’s the real genius of Chrono Trigger: it can offer us two different answers to its central thematic question--it can show us two different but equally persuasive worlds, and that it can do it both through story and through gameplay. The reason that Chrono Trigger can do all of this is because Chrono Trigger is really two different games.

Those two games are what we’ll refer to as the Tragedy of the Entity, and the Comedy of the Sages. It’s important to note that this division is not simply a literary one; not only are the two parts of Chrono Trigger written differently, but they also play very differently, or else the difference wouldn’t be very ingenious at all. This is why the game is so special, because the designers knew that if they could use the gameplay to preserve and embellish the surprises in the plot, they would have accomplished a unique form of storytelling, idiosyncratic to their craft. Accordingly, this Reverse Design will analyze how Chrono Trigger was created so as to deceive, surprise and delight the player, quest by quest, dungeon by dungeon, and scene by scene. But first, a brief overview.

The Tragedy of the Entity

The first game, the Tragedy of the Entity, is a guided tour of the tragic history of the planet and its many eradicated inhabitants; it takes place across the first 13--very linear--quests. This game is tragic in the colloquial sense of the term; it’s a sad and affecting story. It’s also tragic in the classical sense of the term; the hero of the story is propelled by a tragic flaw towards his inevitable doom. What makes Chrono Trigger interesting, in this regard, is that the Crono’s tragic flaw--and really his only characteristic at all--is that he’s the hero, and player avatar, in a videogame where the objective is defeating an overpowering evil. Really, he has no choice; it is his destiny to face the monster, whether he can defeat it or not. The only real difference is that in the case where he cannot defeat said monster, instead of a game over screen and a reset button, the stakes of his loss (specifically, at the Ocean Palace in quest 12) are carried out in the story of the game; that is the reason Crono dies. Of course, we’ll dig deeper into this as we go.

The problem with this kind of tragic inevitability is that while readers, viewers and listeners are accustomed to the feeling of powerlessness that a tragedy instills, gamers and players are most certainly not. In order to keep players engaged without compromising their vision of a tragic story, Chrono Trigger’s designers set about continually deceiving and surprising the player using various methods. If the players are always a little bit off-balance, they won’t realize the oncoming tragedy until they’re already hooked. The moment of triumph for the designers is when the tragedy seems at once surprising and inevitable. This takes more than just good writing, however; it also takes very clever use of the aspect that makes videogames unique: gameplay.

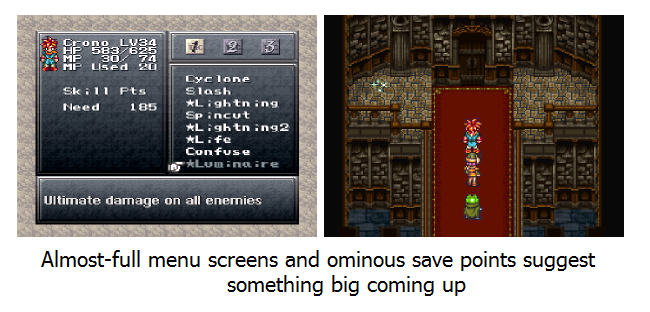

Chrono Trigger has the distinct advantage of speaking two languages: it is a game that tells a story. Game designers, independent of game writers, communicate a lot to their players with things like dungeon pacing, the difficulty level of bosses, seeing towns that have not yet been explored, teaching skills, or even through the interface!

The great trick of the Tragedy of the Entity is that in one language it tells players that they are victorious: they win battles, collect items, level up, jump through time. But in another language it tells them--subtly--that everything they’re doing is actually meaningless (to say nothing of entirely linear). At almost every turn the party’s efforts to change the past are blown away by Lavos, who warps history to suit himself instead. The player really ought to have realized that the inevitable showdown with Lavos might not go so well for them. But the player doesn’t realize this, because the game keeps him off balance, using a variety of gameplay and story techniques. By the time the player figures it out, it’s already too late. The feeling that the party’s defeat was inevitable breaks on the player as a grim and surprising realization.

The Comedy of the Sages

The second game that makes up the content of Chrono Trigger is the Comedy of the Sages, which begins at Death Peak. This is a comedy in the classical sense of the word, a dramatic work with a (reasonably) happy ending. Specifically, the Comedy of the Sages is a comedy of intervention, a kind of comedy with a long historical tradition. In a comedy of intervention, the dramatic action comes close to tragedy, but the characters are saved by a concerned outsider. Everything from Euripides’ Alcestis to Shakespeare’s Much Ado about Nothing are comedies of intervention. Part of the deceptive nature of Chrono Trigger is that the comedy of intervention begins only after the tragedy is complete. That’s the beauty of time travel, after all. (And it bears a lot of comparisons to another irregular, time-travelling comedy of intervention, Back to the Future.)

The remarkable thing about Chrono Trigger’s game design is that the intervention--by the three Gurus of Zeal--not only changes the tone of the story but also changes the style of the gameplay. During the Tragedy of the Entity, the game was almost entirely linear. The party moved from point to point and era to era with hardly any alternatives at all. During the Comedy of the Sages, thanks to Balthasar’s time machine and Gaspar’s vision of the various helpful quests, it’s possible to move freely through time, tackling the quests in any order that the player wishes. Moreover, the style of the quests changes. Previously, all quests were, more or less, a direct attempt to find and defeat Lavos or his alleged creator, Magus. Those quests were mostly map-town-dungeon-portal, map-town-dungeon-portal, and so on. The results of those quests were historically insignificant; the player changed nothing from one era to the next. In the second game, the quests are not about destroying Lavos but about helping more minor bystanders, usually people who are connected to a party member somehow. The quests break the earlier cycle, and can often be short and involve lots of time travel puzzles. And the best part is that those quests have real, tangible historical impact.

We’re going to deconstruct exactly how the first part of Chrono Trigger uses differing gameplay and story cues to create a surprising, yet seemingly inevitable tragedy. After that, we’ll deconstruct how the second part of the game, the Comedy of the Sages undoes the damage of the earlier tragedy by giving the player the game they thought they were playing in the first place.

Quests and Their Design

To speak comparatively, our study of Final Fantasy 6 revealed that the essential design elements of that game were like a cauldron of boiling water. You can see the steam and hear the bubbling, but if you want to know the cause of it all, you have to get down on your hands and knees to look beneath and see the fire that supplies the heat. It’s harder to see at first, but the enjoyable part of the game arises from the mathematical nuances, the subtle artistic flourishes, and delicately balanced structure that your average player will rarely notice. They have no idea what’s going on down there, because they’re not supposed to see it. It can be a mess of information that a player rarely needs, and the real show is the product of all this heat.

Chrono Trigger is more like a very fine mosaic. Everything you need to know about Chrono Trigger is right on the surface, and every individual piece of information is fairly simple, but the various pieces are glued together so finely that sometimes it’s difficult to know where one begins and the other ends. The party’s first arrival in the Kingdom of Zeal is a good example of this. That first trip is amazing; but it’s likely that the player doesn’t even realize that the Zeal section completely breaks the pattern the game has established--it has no dungeons, no explicit quest, and only one real scripted scene. That is just one example of the genius of Chrono Trigger; because it is so artfully made, players overlook the seams and cracks in the mosaic, and instead see only the larger picture. The truth, however, is that the cracks are plain to see for anyone who’s looking for them. It’s just a matter of breaking the game down into smaller pieces.

The fundamental pieces of Chrono Trigger are quests. All RPGs are filled with quests, but sometimes those quests can be vague, misleading, poorly crafted, or even just tedious. Sometimes the quests are just filler material between story sections. In Chrono Trigger, the quests are very tightly written, and usually cleverly designed. Part of why Chrono Trigger is such a masterpiece is that the designers were very careful to introduce, prepare and then test every long-term skill the player would need to use to achieve success going forward in the game. If the player didn’t develop these skills on time, the pacing of the game would be ruined, and the overall narrative spell would be broken. Accordingly, above every quest description is a summary of the core design ideas introduced, developed or tested in that section--mostly player skills but some other pacing elements as well.

Note that this is an attempt to completely reverse-engineer the design of Chrono Trigger, and so there are many components to the analysis that don’t explicitly support the thesis of consonance between the theme and the gameplay mechanics. Obviously some things in the game needed to be simple, orthodox RPG design ideas that allow the game to be playable before it can be artful. But regardless of the support these elements lend or don’t lend to the theme, the game takes pains to pace itself really well. There are lots of places in quest descriptions where we highlight a good design idea and how it is executed, just for the sake of examining good design. That stuff is important too!