What I Talk about, When I Talk about Game Narrative.

The Short Version This section deals with the construction of plot when it has to meet the demands of a game, much of which has already been established before writing began. With statistical analysis of the script and who speaks it, obvious design choices appear. Final Fantasy 6 was created around a roster of characters developed well before most of the other aspects of the game. Moreover, there are a number of tropes common to the FF series which had to reappear. What the FF6 team did to work around this was to center their plot around a villain and an event, so as to allow 14 different characters to have individual stories without making the game seem disconnected. This also made communicating the thematic messages of the game easy, without seeming overbearing or last-minute.

This is not a literary critique of the plot of Final Fantasy 6. Rather, this is a look at how the design team chose to structure their plot and develop their characters so as to accomodate the game which was the real product. My general observation, backed up by a few sourced facts, is that most of the design features of the game--specifically the roster of characters--came first, and a plot was assembled from the pieces. I'd argue that as far as this is the case, the plot came out pretty well, being written and influenced by numerous people.

Many critics assume FF6, like many JRPGs of the 90s, survives not in spite of its flaws, but because of its flaws. That is, the critic assumes that the masses love the game because it was unsophisticated juvenile crap, which is what the masses love. Or at the very least that's what they loved when this game came out, years ago, and nostalgia alone has preserved it. Real art games began with Ico or Bioshock or something like that--if games can be art at all.Such an assumption ignores a lot, and would overlook many of the lessons we might learn from FF6. In 1994, the Final Fantasy team didn't have the kind of creative latitude, industry development and standards, or money that the Ico or Bioshock teams had. This is not an apology for the shortcomings of FF6, but rather an admonition that we really ought to examine how FF6 does a lot with a little. In many cases, FF6 is able to convey meaning, emotion and experience very judiciously. That is to say, because the creators had fairly tight restraints on the product they had to make, they were very creative and often quite sly about how they made their game artistically appealing and complex.

The goal, of course, is to try and identify all those great tricks, so that all of us can understand more about what makes a great game, and also future designers can use these tricks to make their games better.

Quests and Quest Structures

Like with everything else, we should probably look at the story and script from the highest level first. In the most general sense, what is the story about, and how does it communicate that? Since the game is an RPG, one thing we can be sure of is that there is an over-arching quest, and it's probably made up of several smaller quests. So what is the quest? Saving the world is the quick answer, and there are certainly elements of that in the game. But I think that the story subverts the traditional save-the-world-from-destruction trope to a certain degree.

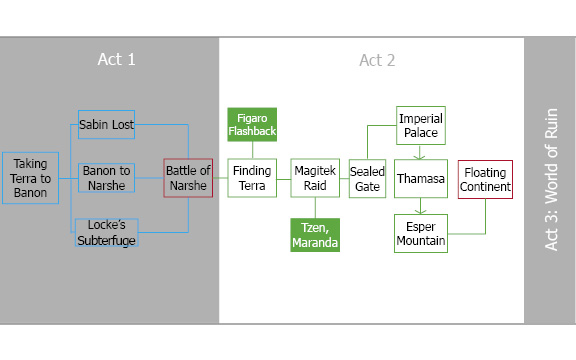

(A brief explanation: I divide the whole game into three main parts. Each part begins with someone waking up. Terra wakes up in Arvis' house, after the prologue, beginning part one. Locke wakes up in the same bed, after Terra is revealed to be an Esper, beginning part two. Part three is more obvious: the beginning of the World of Ruin. But, if you notice, that also begins with someone waking up: Celes, on the Solitary Island.)

Obviously, the world ends halfway through the game. It's not most literal end-of-everything Armageddon, but it certainly proceeds in that direction. Kefka probably could have ended everything, or at least every human life, but he doesn't. (There's a good reason for that, in Kefka's character section.) Still, as several characters and NPCs remark, the world is only getting worse after the catastrophe. The end may be soon.

Another way to look at this question is to examine how many quests are about saving the world. This is an RPG after all, and there are quests, whether they're announced or not. As I see it, there is no point in the game where the quest is to save the world from destruction. Certainly the second half of the World of Balance is about saving the world from oppression, but hardly destruction. Gestahl wants to rule, and says as much. The fact is, however, that the world ends on account of a split-second decision by Kefka, who had no idea what the results of his actions would be--although he didn't really care either way. If he hadn't decided--until that moment--to end the world, how could there ever be a quest to prevent him?

The final quest, to kill Kefka, would seem to be the world-saving heroic act. I contend, however, that it's actually not. Killing Kefka means removing a crazed demigod from power, but there's absolutely no guarantee that this will restore balance to the world. Rather, just before the final showdown, each character tells Kefka what gives him or her the strength to go on living in a ruined world. Inasmuch as this is the structural "conclusion" of the game, it stands to reason that the game is "about" the characters finding their strength and reasons for living in a broken world. So, in a sense, the quest is not to save the world, but to struggle with and overcome the tragedies and monsters that inevitably arise in it.

Several former Squaresoft employees reported that one of the first steps in creating the game was creating the roster of characters. If so, it holds that the story is really about the characters, their reaciton to a central event (the unbalancing of the world), and their struggle to maintain hope and resolve. There's no meaningful distinction between the construction of the narrative and the design of the game; they were built together in order to accomodate the characters. The rest of the design reflects this as well.

How to Break Your Word Count Tool

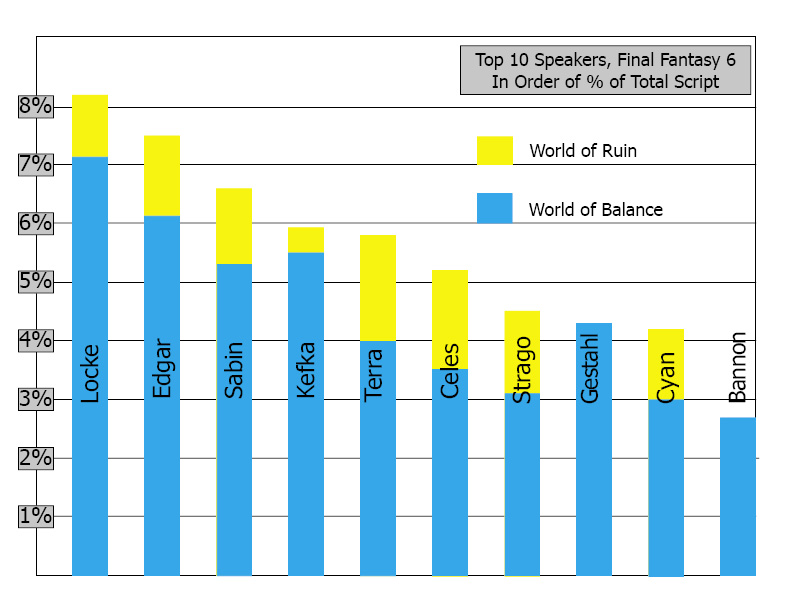

Another way to look at the story objectively: who tells it? There are fourteen playable characters (twelve of whom say something meaningful) and two important antagonists, and a host of supporting characters. Surely the proportions of their speech should tell us something about how the story was not just written, but designed for the game.

A quick note on my methods: I counted all mandatory script scenes in the World of Balance, and everything in the World of Ruin (since very little is mandatory, but you don't have much of a game otherwise). That means I've left a few things out here or there that I considered to be outside the scope of the "script". Thus, I do not give my exact word counts. (I can't imagine what use exact word counts would be anyway.) What I do preserve are the proportions. Even If I were to add every conceivable jot of character dialogue here, the proportions would change very little. One final note: I used the original Woolsey translation. While there are differences in nuance between that and the GBA port, there aren't substantial differences in length.

I'd wager most people didn't expect to find that Locke speaks the most. Certainly, few think of him as the main character. It does make sense from a certain perspective that he speaks the most: he shows up early in the plot, and is very talkative. The same is true for Edgar, who shows up early and frequently acts as a leader; it makes sense--he's a king, he's got a lot of practice at it. On the other hand, Shadow shows up very early, but he's extremely laconic, so his totals are low. But who is the main character? It's not clear from this angle.

The most interesting aspect of this analysis, to me, is that Kefka is the fourth-highest source of dialogue. In the World of Balance, where most of the plot happens, he's the third-highest source of dialogue. (He'd probably maintain his 3rd spot if he appeared anywhere besides the final dungeon in the World of Ruin.) He's also the first person--at all--to appear on screen, briefly in the prologue. This doesn't happen too often. Consider how much fewer were Sephiroth's lines, or Exdeath's, or Ultimecia's or even those of Zemus. Kefka is unusual among Final Fantasy villains, and indeed among RPG villains in general.

Why make Kefka such a dominant presence in the game? One reason must be that with fourteen playable characters, it's difficult to center the plot on one issue that would be meaningful for each member. Kefka's big personality, his grandiose and cruel actions, his trademark laugh; they give the player and the characters focus. A cold, calculating villain picks his battles and doesn't fight everyone. Kefka, being like a literal psychopath, is wild and unpredictable. He's chaotic, talented, and dangerous. It's not hard to believe that everyone in the party--even members of his own faction, have problems with Kefka. It's not hard to believe that everyone in the world would be right to fear him. You cannot be on Kefka's side. What side is he even on? Kefka embodies disaster: impersonal, chaotic, incomprehensible. Much like a disaster, he brings disparate people together, including the 14 player characters.

Kefka also frames the theme of the game in a question during the final encounter. He says, "Why do people rebuild things they know are going to be destroyed? Why do people cling to life when they know they can't live forever?" It's kind of a daunting question, isn't it? I'd challenge anyone to pick a quote from a videogame that's as obviously (and effectively) directed at the player. And I'd challenge them to find a villain who can say it so convincingly in-character. It's a rare feat. So it's not really fair to say of the game that it's another in a long line of generic, world-saving adventures. The heroes are not succeeding in brilliant fashion; they're making do with the situation presented to them. (The NPC chatter reinforces this thematic approach quite obviously.) This is clearly reflected in the quest structure of the second half. Virtually every character has a quest about dealing with something they've lost. And it's definitely the characters that make the story, Kefka included.

Useless but fun trivia bits! About 0.5% of the script was delivered in written notes; about 0.6% was delivered as song. Espers spoke about 3.8% of the dialogue, other non-humans spoke about 2.3%. And how about this bigtime effort: dead characters spoke 2.3% of the dialogue, despite their obvious impairment. About 7.7% of the script--a very large chunk--was spoken by an actor only identified by quotation marks, so as to allow any party combination to speak the same words, of course. And last but not least, omniscient narration gives us roughly 2.45% of the script.

Previous - Introduction to FF6 and the Reverse Design Process.

Next - The Rule of Three: Examining the Balance of Plot, Exploration and Combat.