NPC Irony & The Sociology of an Imaginary World

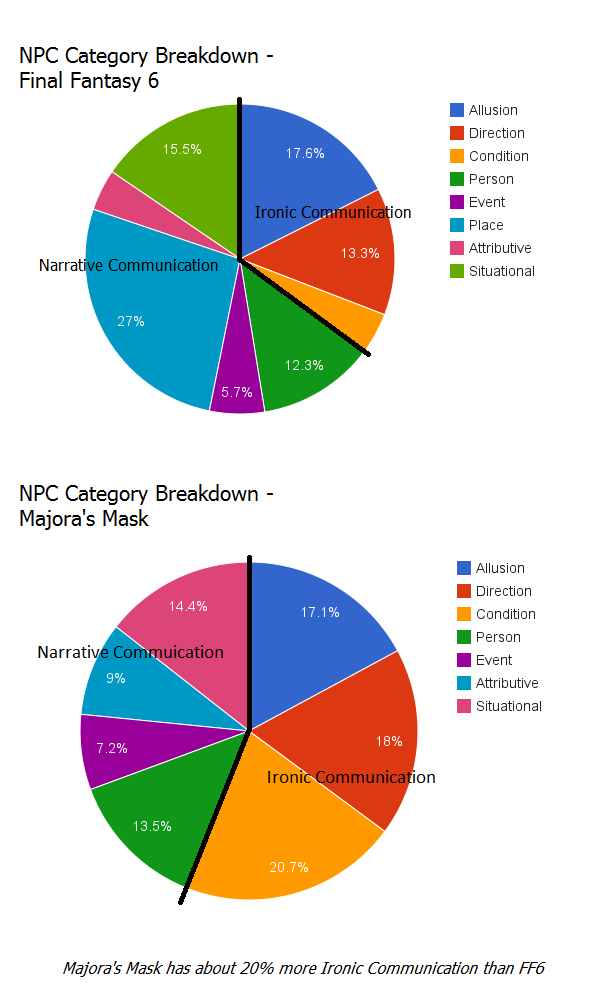

The Short Version This section of the chapter is a kind of sociology of the videogame world, focusing on the role of NPCs. The communications coming from NPCs tend to fall into two groups: ironic communication and narrative communication. Ironic communications are veiled instructions for the game, written so as to not break the narrative spell. (I.e. "I hear that dinosaurs hate lightning!") Narrative communications are additions to the script, which embellish the events, characters, places and things in the virtual world. ("You grew up in this village.") This section divides NPCs by function, across the two categories above and several different sub-categories. Additionally, FF6's NPC content is compared statistically with two other games: Majora's Mask and Tales of Symphonia.

One of the most important ways that a designer (rather than just a writer) communicates with the player is through Non-Player Characters, or as we know and love them, NPCs. One of the nice things about studying the design of Final Fantasy 6 is that although NPCs have become more robust technologically since 1994, their purpose has hardly changed at all. NPCs still exist to do the same things they've always done in RPGs. So the question is, then, what are NPCs there to do? In short, NPCs are there to provide information about the game. There are many different kinds of information that NPCs need to provide, from gameplay tips to story embellishments, and everything in between. As I see it, these tips break down into two essential categories: ironic communication and narrative communication. Ironic communication, or as I call it NPC irony is based on the need for the creators to tell the player a lot of information about the game and how to play it. They can't simply break the narrative spell they've cast by having every NPC be an instruction manual. Accordingly, it is important for designers to learn how to mask their gameplay instructions with narrative pretext.

For example, if you first entered a town and the NPCs there said things like, "Ghosts don't really exist!" and "I don't really believe in them, but I hear ghosts are afraid of fire," what do you immediately know? Of course, it's obvious that you're going to be fighting ghosts in the very near future, and that you should bring fire-elemental attacks. The NPCs didn't literally say that, but the designer has communicated it to you, clearly. And, as Bender reminds us, any time someone says one thing, but means something other than what's literally stated, it's a form of irony. It's the same in any RPG, and of course is true in FF6.

There are a lot of fine distinctions between different kinds of ironic and narrative information that NPCs need to convey. The way we classify them depends not on how the NPC says something, because that can be an ironic deception, but on what the designers are trying to commuincate to us. The information the designers give or imply determines the category. As I see it, NPC communications can be broken down into categories like so, starting with the ironic categories:

Direction

Directions are the most obvious form of communication from the designer, given through NPCs. Directions are, naturally, direct instructions about an action that the player ought to take. While they don't necessarily need to be ironic, they can be. A man in Narshe instructs you to take his treasures (in the house to the right) before someone less reputable tries to use them. That's a pretty straightforward direction, yet it still falls under the category of NPC irony, because it's player instructions couched in player character instructions.

Similarly, if you're outside a dungeon and someone says, "This is the haunted temple, don't go in--it's dangerous!" the designer is basically telling you: "This is a dungeon, make sure you're ready before going in." It's a little more obviously ironic this time, in that what the character tells you is very clearly the opposite of what the designer is trying to communicate with you. The ironic veil is usually pretty thin with a direction, but it's fairly essential, as it would be too easy for everything in the game to become a bland manual.

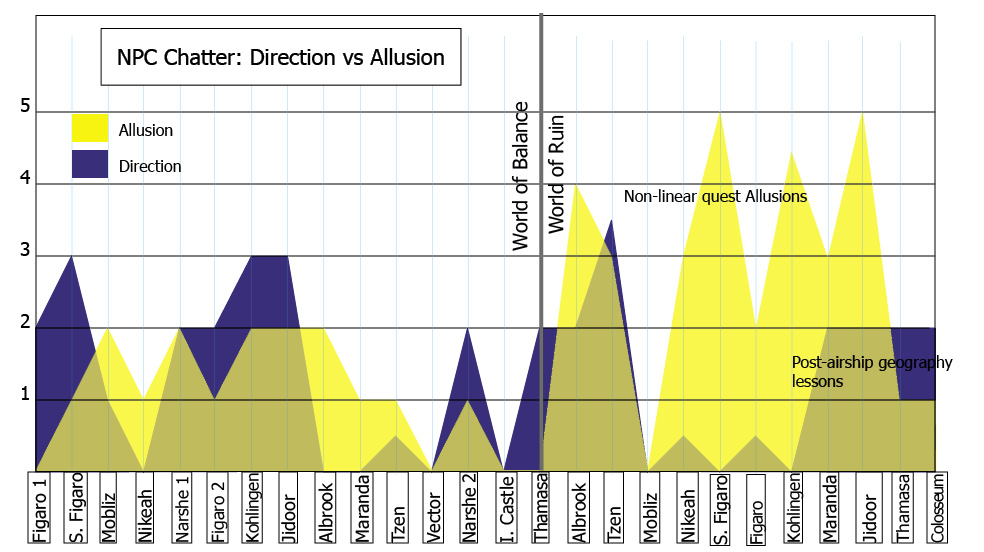

A good example of NPC irony and directions is in Kohlingen, in the WoB. An NPC asks, "You a friend of Locke's? He always stops by Rachel's house when he comes here!" This is essentially a direction: if you bring Locke to this location, something interesting will happen. In this case it's a flashback. It's ironic because the characters have no use for this information, but the player will quickly realize that the designer is communicating the presence of an optional story segment. A less ironic example is in Thamasa where one of the NPCs informs you that Strago is trained as a Blue Mage, and can learn monster attacks. There are numerous instances of both ironic and unironic direction, although direction becomes less common in the WoR, where it is often replaced by allusion.

Allusion

Allusions are more highly ironic directions, with one special requirement: they must leave out one essential portion of the directions, either who, how, what, or where, or when but usually not more than one of those. In that sense, allusions are a kind of puzzle that the player needs to figure out by investigating. For instance, one NPC remarks a quest that will take place at Doma Castle.

Demons, Doma Castle? Sounds like fun! He tells you the what (demons), the where (Doma Castle), the how (sleeping there), but not the who. Cyan needs to be in the party for it to happen; this fact needs to be intuited by the player, but it's not an enormous leap to make, considering that Doma is Cyan's home. That gap, however, is the defining aspect of an NPC allusion, and what separates it from a direction. Ironic directions may tell you how to do something obliquely, but they tend to tell you everything you need to know. Allusions make the act of deciphering the quest part of the quest itself.

Allusive information is actually worthwhile specifically because it's opaque gameplay data. It should come as no surprise that gamers like to figure things out for themselves, and allusive communications are no different. NPC allusions are like puzzles, where the player has to figure out what the game designer is trying to tell them. For instance, the last imperial trooper at the colosseum tells you "Talk to the emperor twice." By the time he tells you this, the Emperor is very clearly dead. This allusion is actually referring to Emperor Gestahl's portrait in Owzer's house, which can be examined by using the "talk" button. (There's an NPC in Jidoor who proclaims: "I saw the emperor recently! Well, a painting of him.") Examining it twice reveals yet another allusion: a letter telling you that a treasure is hidden "where the mountains form a star." There's no obvious instruction, although finding the mountains in question is relatively easy. This is a two-step allusion that actually points to a major dungeon with a recoverable character, important Esper, and lots of treasure inside it.

I have observed a fairly widespread rule for making NPC allusions more effective and noticeable (the NPC allusions rule). The rule is: the number of NPCs in a single town/area who provide allusions on the same topic is inversely proportional to the proximity in space and time of the alluded object. Or, in other words, if a bunch of people are talking about the same vague thing in a town, expect that thing to be available to you soon, possibly now--although you might have to go a little bit out of your way to get it. The most shining example of this is the path to acquiring the optional character, Mog. You can see below.

On the other hand there are many things which are much rarer. The Atma weapon, for instance, is mentioned only once. The clue is that it's mentioned in a town close to a large dungeon that is only open once. You're probably not going to get the weapon on your first playthrough, unless you're a dilligent dungeoner. There are, however, many things that are mentioned once in the WoR that, while puzzling, are available forever. Since you can do them in any order, however, there's never a cluster of allusions like in the World of Balance. Rather, these allusions are scattered in various towns, and if you don't talk to everyone, you won't find them! I think this is actually one of the points where FF6 shines: you absolutely do not need a strategy guide to accomplish everything in the game. Somewhere there is an NPC who will give you the hint you need to find all the secrets in the game.

Condition

Conditions are NPC statements about the status of the level of interactivity of a gameplay element. A simple, unironic condition would be something like, "This store is only open at night." That is, access to a gameplay element is limited to the condition of it being nighttime. Conditions have a large range, and can often be highly ironic. A man blocking the only exit of a room, saying, "Can I help you?" is actually a condition, just a highly ironic one. The designer is communicating: "this room cannot be exited until some condition game environment changes, but you'll have to look elsewhere to find out what." A few, finer criteria for condition:

-Conditions do not indicate any possibility for direct player action to change the condition, or else it's an allusion or direction.

-Satisfaction of the condition is often undisclosed: the game tells the player to "go do something else, and come back when the condition is changed, as a consequence of your actions elsewhere."

-Often a condition is a signal for a player to simply wait. Sometimes that means the player doesn't even recognize a condition when they encounter it, and only benefits from the condition when they remember the conditional statement, and go check in at the location where it was issued much later.

Conditional information is often opaque, because it's frequently about things that you cannot do when you encounter it. If you go to the town of Thamasa too early, for example, nobody will sell you any goods. The shopkeepers say, "I've never seen you before," and someone in the town explains that the innkeeper doesn't like strangers. "Yes," you automatically think, "but perhaps they've met my friend: money."

Narrative NPC Chatter: Reactions

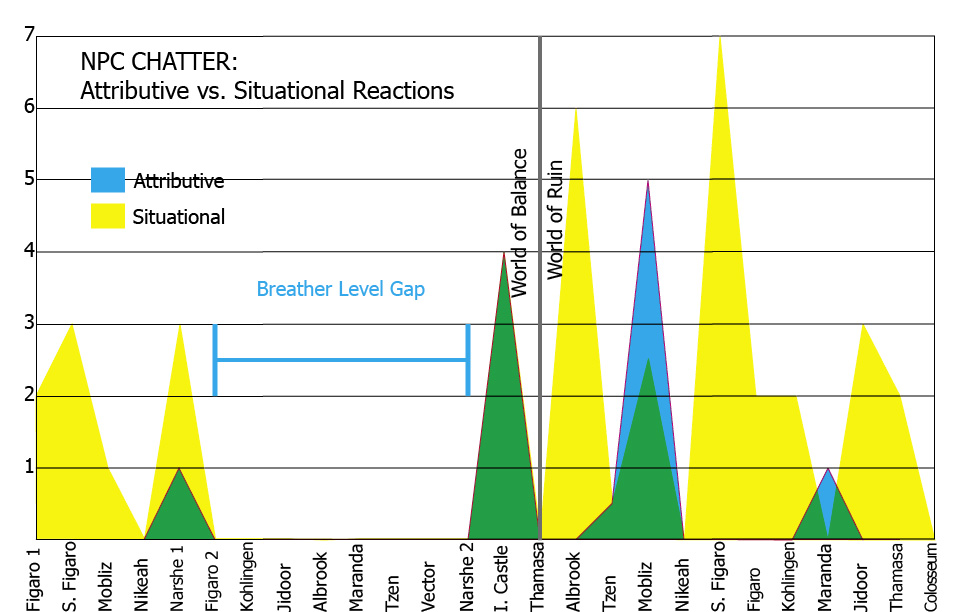

Reactions are a class of narrative NPC dialogue that emphasize the player's agency and participation in the world of the game. They fall into two categories, both unironic narrative, accordingly. "Reaction - Attributive" is the NPCs way of speaking directly to the player characters for what they've done. "Reaction - Situational" is how the NPCs reflect their perception of what's happening in the world that changes around the player.

Reaction - Situational

These are reactions to game states that the player characters also endure, but which the speaking NPC does not believe that the characters caused. The end of the world happened to everyone, but as far as everyone knows it was Kefka's fault, so nobody blames the party members. Although (see the attributive description) nobody seems to believe the party members are doing much about it either.

Another very important criteria is that the "situation" in question be ongoing or have long-lasting impact. "I lost my family in the war," is not a reaction, because it was about something that happened in the past, and while it's a nice narrative touch, it's not something the player characters have to live with, usually. NPCs remarking a limited scope event that doesn't continue are speaking under the "expansion - event" category. I admit the line is not perfectly clear, and with more development better criteria will be refined out of it.

Situational reaction is hugely important in FF6. Many people react situationally to Kefka's destruction of the world--in fact it's the dominant form of narrative chatter in the WoR. Many of those NPCs, however, react positively, mocking Kefka and avowing hope in spite of the ongoing ruin of the world, which fits right in with the themes of the game.

Reaction - Attributive

An attributive reaction occurs when an NPC reacts to your direct agency with knowledge that you've done it. The purpose of an attributive reaction is to reinforce the players' sense of their own agency in the world. The best example I can think of is in Oblivion, when people remark, "Hey, you're the champion of the arena!" or "You're the Gray Fox!" Simpler versions might just be an NPC involved in a quest saying, "Thanks!" You've done something in-game, and they react to it. Fame and infamy are both important factors in attributive reactions, and can be used to procedurally queue reactions to your list of accomplishments.

In FF6, these reactions are fairly few, and are heavily concentrated in two areas: Mobliz and the Imperial Castle. In ruined Mobliz, all the children thank you for helping Terra defend them. They've been through hell, they're not proud, and so it makes sense for them to thank you. In the Imperial Castle a number of soldiers react to your status as their opponent and attack or insult you, although many are sympathetic and regretful as well.

Part of the thematic emphasis of the game, however, is built into the relative lack of recognition for the heroes. (There are about three times more situational reactions in the WoR than there are attributive reactions.) Considering how much situational reaction there is in the WoR, it's poignant that almost nobody speaks to the player in an attributive way. In a sense, the players are going through all of the same struggle that everyone else is. In the WoR, every is made equal by their shared hardship, and they all press on.

Narrative NPC Chatter: Expansions

Expansions are additional narrative information, plot details, characterizations, background, history etc, given through NPCs. Generally, these are completely unironic, although in certain cases they are ironic in the traditional sense (and not the NPC-specific sense). Basically, expansions are embellishments of the story as it is being told through the scripted sequences and cutscenes.

Expansion - Event

An expansion - event categorization is tricky, as it is often confused with reaction - situation. Expansions are merely additions to the scripted narrative-- not reactions to the player's agent contributions to the game. Therefore an event expansion must be about an event in which the player played no role, AND (important!) which the player does not endure. For example, everyone in the world (including the player characters) endured and continues to endure the cataclysmic imbalance that Kefka created, so NPCs will not expand on this event. Rather, they will react to this event, to reinforce the image of a dynamic world that is changing as the player progresses through it. The War of the Magi, however, is an event that happened long in the past. It is mentioned in the script, but NPCs will elaborate some of the details not mentioned in the plot. That kind of elaboration is event expansion. Similarly, many mentions of future events are expansions upon their implications.

Generally, NPCs expand upon events that are over by the time players arrive, or about narrative events that are certain to come in the future. It makes sense that, early in a game, there will be a lot of event expansion by NPCs. Most of history--including fictional history--is made up of summations of events. These events, having happened before the game, can't really be reactions. Thus, when NPCs mull them over, they're really just embellishing events that don't happen on-screen.

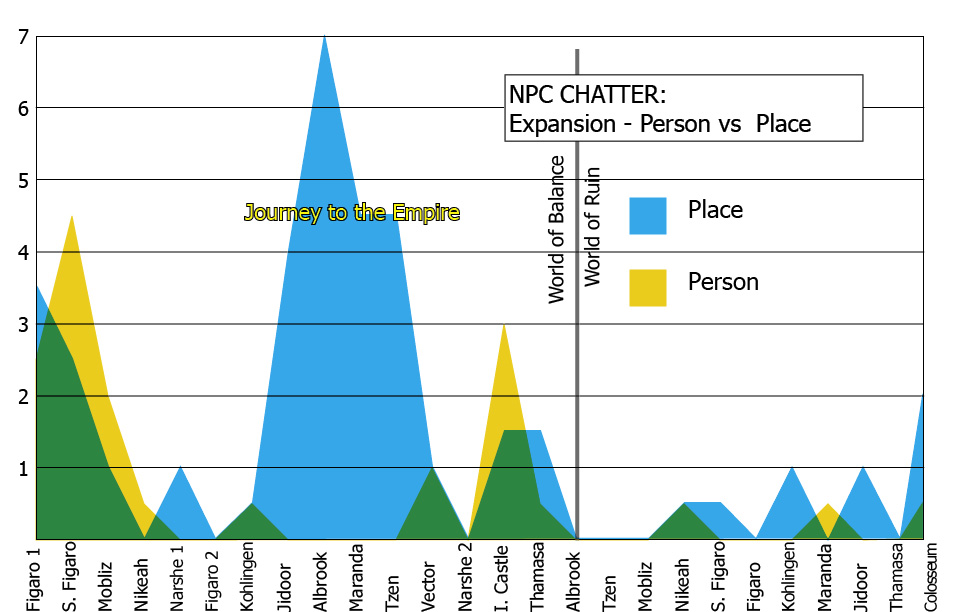

Expansion - Person

Characterization is an enormously important thing, especially in a game with a large roster of playable characters. Accordingly, whenever an NPC provides extra background about one of the characters in the game, it's noteworthy. Generally, these expansions are obvious and direct. Because of the large roster of characters, personal expansions are very frequent in the early portion of the game, although they tail off significantly as the game goes on. Some of this may be because the few characterizations in the second half of the game are actually embedded in allusions that lead the player toward the recovery of scattered allies.

Expansion - Place

In a time when game graphics and memory were not enough to support spawling, full-scale towns and cities, NPCs were a necessary part of giving a place a feel. More than just providing the character of citizens, NPCs were necessary for describing things in towns that were not possible with technology as it was. Time and technology have marched on, and in the sprawling metropolises of modern games, NPCs are often used for giving directions (which, of course, are a different category) more than they are for characterizing the place itself.

In FF6, place expansions were frequent and necessary. Indeed, place expansions are the most frequent kind of NPC chatter anywhere, although this is partially due to an imbalance on the Imperial continent. For its time, the game world of FF6 was massive, and it would have been impossible for it to be brought to life without considerable information about its contents, history, and geography delivered by an easy, efficient source.

Expansion - Thing

More or less exactly what it says on the tin, this category describes NPC chatter that is about an object, faction, phenomenon or other thing. This can be slightly deceptive, however. Chatter about gameplay-important objects will often fall into the categories of allusion or direction. Narrative chatter on the same subject is usually limited to lore about a thing.

In FF6, there is almost no use of expansions on things. This is principall y because the "things" around which much of the plot revolves are actually people: Espers. Because there are, in my judgment, only two instances of clear "thing" expansions in the whole game, I have left that category out of my analysis as being statistically insignificant.

A Survey of NPC Chatter Data

Looking at the game as a whole, it's clear that NPCs are going to provide more narrative expansion than ironically disguised information, although there's a significant amount of both. Colleague Dan Fischbach ran a similar analysis on Majora's Mask, and found that that game differed markedly. It's interesting that of all the ironic chatter in FF6, there are mostly directions and allusions, and not as much condition as I would have expected. I feel like I'm always being given conditional information by my RPGs. Majora's mask (see below) is just swimming in NPC irony. That makes sense, though, doesn't it? Everything in a Zelda game is a kind of puzzle--certainly more so than your average FF title. There's hardly a room in a Zelda game--dungeon or town--where the players don't take a good, hard look around for hidden treasure. So of course there are more NPCs carrying hints, conditions and directions. How would the game even be possible without them?

From a narrative point of view, another colleague looked at the early portion of Tales of Symphonia. Interestingly, the NPCs in the early part of the game game were much more invested in event expansions than at any point in FF6. If you know ToS's plot, this makes sense, as it revolves around a quasi-religious quest initiated as a regular rite. ToS also doesn't have to introduce quite so many people quite so quickly, and so as a function of their designs and plots, the two games differ.

Trends over Time

There's an interesting gap occurs during the quest to get Terra. This quest acts as a kind of narrative lacuna: not much happens plot-wise, the player doesn't have to do too much, and consequently there's nothing for the NPCs to react to.

Some of this is also abetted by the introduction of new towns, and with those towns, new expository expansions and characterizations. In essence, the NPCs are too busy explaining things to you that they can't react to the plot. This quest (as mentioned before) is also kind of a "breather level" which allows the players to process the plot as it has happened so far, and to be ready when the next chapter provides much more of it. You can also see, on the graph above, how the NPC chatter reflects the thematic concerns of the game. Situational reactions shoot up during the WoR, but aside from one primary instance, attributive reactions do not.

What and whom the NPCs explain and react to over the course of the game is hugely important for understanding the thematic significance of the game. For example, take a look at the graph of person vs place expansions.

It's not surprising that there's a lot of personal expansion early on, and one might expect a steady level of place-related infromation the entire time, as new locations open up. This is not the case at all. There's a huge spike of place-related information during the journey to the Imperial continent. This rise in NPC expository activity is a way of showing the harsh condition of life inside Gestahl's empire. The people of the conquered cities remark their mistreatment at the hands of the Imperial Army. It's a great way to characterize a faction, a place, and antagonists who are about to become much more involved in the plot. The extra NPC chatter also comes from having a lot of extra NPCs; that section of the game has three optional towns to visit, each with their own unique gameplay rewards to match.

This spike in NPC narration actually comes full circle back to reactions during the Imperial Palace scene, which you can see on the reactions graph. (It's the densest narrative NPC location in the game.) Many commenters on the game have wondered why it was that Gestahl, who was only lying to catch you off guard, wanted the party to talk to his soldiers. It seemed like a bizarre request--in fact it is a bizarre request, coming from Gestahl. The point of it, I think, was to use NPCs to deliver some thematically important information. Gestahl's army is not unanimously evil, his empire and citizens are not unanimously worthy of reproach. Among his ranks are many people who fought for their country because they believed they had to, because it was the only opportunity available to them. Many of those people feel quite badly about what they've done, what the war did to them. Many of them also harbor considerable hatred for Kefka.

How could this have been communicated in a scripted scene? I don't think it could; I think that talking to the troops in the Imperial Castle is actually a masterful way of thematically setting up the second half, where there is no more Empire, no more war, no more factions. Although there is another battle that the Empire will fight before it ceases to be, it's clear that people on both sides of the war hate it. Everyone--including some of the aggressors--becomes victims of Gestahl's ambition. This is doubly tragic when you consider that directly after having their lives destroyed by war they participated in, many of these people (whom you'll meet again in the WoR) have their world ruined by Kefka. And of course, this turns up in the many situational reactions that appear following the world's destruction.

Trends in Ironic Chatter

The WoR has interesting trends ironic NPC chatter as well, in the way allusions overtake directions, although there are still a good amount of directions. Considering the new geography, how anyone would get started their first time through the WoR without directions is beyond me. And that's what most of the "direction" chatter was--map directions. You can see how those directions are mostly in towns only available via airship.

As for the rise in the number of allusions, and their near-ubiquity, this should come as no surprise. (Poor little Mobliz! No allusions there, for good reason.) Part of the thrill of a non-linear world is feeling like you've put the puzzle together yourself. If the NPC in Thamasa simply said, "There's a bonus character inside the monster on the triangle island," it wouldn't be nearly so fun as when you have figured it out. That intuitive leap is quite a rush. I realize that in the age of the wiki, most game mysteries are dead, but I don't think that's only the fault of lazy designers. When was the last time you played a game where NPCs clued you in to everything you ought to be doing by use of allusion? Maybe if they were doing it more often, we wouldn't all be FAQ junkies. (Alternatively, if we were collecting useful goods that served as synecdochic symbols of our progress instead of multi-colored skulls, maybe we'd be more invested in doing it the right way, too.)

The conclusion I want to make about NPC irony is that designers have a dynamic, in-game manual at their disposal at all times. The character of NPC chatter can and should reflect the thematic climate of a game. It's nice to populate a world with a number of vibrantly different characters, but if those characters don't respond to the world's changes as brought on (directly or indirectly) by the player, they're going to feel like mannequins. If those NPCs don't expand upon the people, places and things brought up in the plot, the player will feel a disconnect between story and gameplay. And if there aren't some marketplace rumors to tell you where to find a dungeon or some nice loot, players are going to spoil half the game by reading a FAQ. Embrace the use of NPCs for ironic and narrative purposes; it can only do your game some good.

Trivia! Just because an NPC is using NPC irony, it doesn't mean they're not also using regular irony. You think that NPCs are recolored often? Well, they are. There are more than 120 different NPCs, but only 56 sprites between them, although a few are only used once. But if you think NPCs have it bad, check out monsters! There are about 105 monsters that get recolored, but there are almost 300 instances of recoloring. Some monsters get recolored 5 times!