Levels, Stats, and Metrics

The Short Version This section examines the level-up system, stat-points and gear of Final Fantasy 6. It is observed that FF6's level and experience system are fairly standard and in line with its non-MMO peers. The growth of EXP intervals between levels is inversely proportional to the growth of player character levels. This, it is stated, is to move the player through the first half of the game quickly, without providing a good place to grind and abuse the ratio of reward / time. An examination of stat points reveals that, because of the diminution of character classes, there is only one truly meaningful native character stat: magic power. Every other meaningful stat contribution is contributed by equippable gear; this gear is analyzed with detail.

We're going to look at the level-up structure of the game, and what it means for the player's experience. There are also a number of useful metrics in this section for measuring the performance of stats, weapons and levels. First, however, I should introduce two stats I use to measure different trends in design. The first stat is actually very simple: RAW. RAW is simply the amount of raw damage done by a character or enemy, ignoring all other variables. RAW is useful for measuring the effect of different factors upon a character's abilities. To figure in enemy defense and damage reduction, I use a different stat called DAE, or damage against the average enemy. This stat shows how effective a character's abilities are against a typical defense, which will suggest how significant various changes in RAW are against aggregate enemy defenses. Because of the standardization of stats in FF6, there are a huge number of enemies within 20% of the average defense, so this is actually very practical data. Also, I should note that almost every attack in the game is subject to random variance. The scope of the random variance isn't terribly large; it might matter to an individual player, but it doesn't matter to overall design trends. I elected, at all times, to show graphs at the highest possible output yielded by random variance for simplicity's sake. Some of my numbers might seem a bit higher than average to anyone looking closely enough, but all of the trends, slopes, percentages, fractions, etc are all accurate. Thus, we should always be able to see the design trends clearly, which is what we're after anyway.

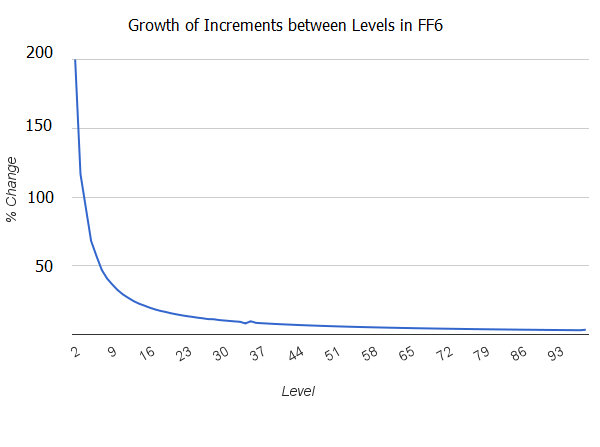

Now, onto the analysis itself. It all begins with a graph:

This is the growth rate of the interval between level-ups in Final Fantasy 6. Some brief slices of explanatory data: to go from character level 29 to 30, a character has to gain 8200 EXP, up by about 10.1% from the last level increment, 7688 EXP. The growth of the increment between levels gets smaller, however. To go from character level 49 to 50 the player needs to gain more EXP (20,816) but that's only up about 6% from the previous level increment. And so the trend continues.

This is a common trend in level-up systems of RPGs. At first I was quite confused by the data. For example take a look at FF5 and FF7, and you see a very similar trend. But it's not just FF titles that do this. Take a look at a very different game like Diablo 2, and you see the same thing!

This is a little counterintuitive at first: why would it become easier to level up late in the game? Doesn't that make the game progressively easier when it should be progressively more challenging? As far as FF6 is concerned, the answer is no. The result of this level up curve is actually that the player characters seem to level-up at a consistent rate, not an accelerating one.

To answer how this is the case, we need to take a brief step back, and see the bigger picture. All level-up systems are founded upon two essential ratios: reward / challenge (R/C) and reward / time (R/T). Most players will recognize this instinctively: the harder a challenge is in an RPG, the greater the reward will be, usually. Obviously there are exceptions to the rule, but this is true much more often than not. In a fair level-up system, the R/C ratio will not vary too widely throughout the game. Challenges will generally yield results close to the player's expectations. The most common instance of this is in battles: EXP rewards should correlate to the difficulty of the battle. As the characters level up, battles get easier and the EXP rewards should become increasingly trivial. This decrease in reward will prompt the player to seek harder challenges that have more relevant amounts of EXP. That's the kind of design that will make sure the player sees a lot of the game.

It is still possible for players to abuse the system by taking advantage of a favorable R/T ratio. That is, players can find exceptionally easy challenges (enemies) and defeat them at such an accelerated pace, that the reward schedule becomes more favorable than normal gameplay. In the early parts of the game, enemies are exceptionally easy, so as to teach players how to use the combat system. (This fact is provable on two objective criteria. The defense of these early enemies is about 25% lower than average, and they have fewer chances to do anything at all during battle, based on the design of their AI.) It would be all too easy for players to take advantage of this necessary ease, and speedily jump several levels ahead of the design.

The level-up structure to which FF6 ascribes avoids the pitfall of early R/T abuse, and also serves a second purpose: to drive the plot. As we saw on page 2, earlier dungeons are bigger and easier. There's also a lot more talking and a lot less treasure in those early dungeons than there are in the second half. Early dungeons need move the plot quite a bit, and the player spends a lot of time in dungeons as a result. If the corresponding early levels (in FF6, anything below 25) had EXP increments between levels as small as the second half of the game, the player might gain many more levels in the first half than in the second. That would make the game feel rather lopsided.

So, for a variety of reasons essential to preserving the design, FF6 and many games like it use a gradually diminishing growth rate in the increments between level-ups. Of these reasons, however, I would say that maintaining a stable R/T ratio is the cornerstone, as games in other franchises--beyond, even, what I've mentioned here--seem to obey it as well.

LEVELS AND STATS

If a picture is worth a thousand words, an excel graph is worth a thousand words after taxes. The FF development team was presented with a problem: they needed to make stats meaningful, without breaking their game overarching game design themes. The goal was, as always, to make characters play differently, but not too differently. After all, most of the game is spent controlling one, very select party. The biggest dungeons, however, involve controlling two and three parties of characters. Characters can't play too differently, or those challenges become extremely annoying, if not impossible. And what makes an RPG character play a certain role? Stats!

As it is, most character stats in FF6 don't do much in the absence of equipment. Stamina, for instance, requires an extensive amount of investment in order to reap half the benefit you get from a single accessory. Investing in the speed stat, meaningfully, requires that a character eschew all other stats; it's problematic, and the effect could be achieved with a simple cast of Haste 2. HP and MP investments are okay, although they don't increase the overall durability of a character that much--a fact that we'll discuss on the next page.

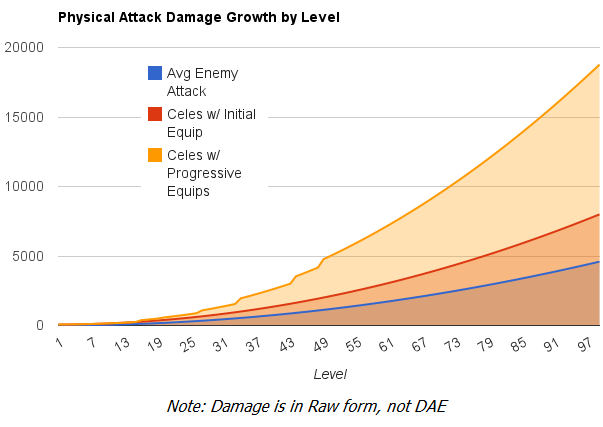

What the designers did was to emphasize two things instead of stats: one of them was equipment, and the other was character levels. Below is a graph charting the relative importance of levels and equipment in modifying physical attack damage.

The top line is weapon upgrades; you can see how the slope is steeper than anything else below. Weapon upgrades give not only more power, but each weapon upgrade gives a larger proportion of power than the previous weapon. Not so much with pure levels. The second (red) line shows how one weapon's output scales across levels. The slope gets steeper, but much more slowly, and the absolute amount of endgame damage is, of course, nowhere near its weapon-upgraded counterpart.

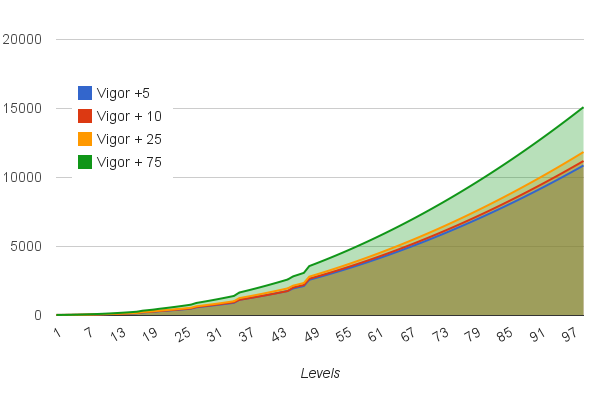

But, okay, this proves nothing on its own. Because the game's weapons are all pre-constructed and cannot be modified, we can assume that any inflation based on the acquisition of weapons is figured into the difficulty. It's all just inflation. If we want to know more about the system and how players master it, we allso need to isolate the stat that controls the power of physical damage: vigor. A similar trend emerges, though:

It's clear that small differences in vigor--the kind of differences that are actually possible without immense planning and power leveling--have hardly any effect at all. Even at +75 vigor, which takes quite a bit of planning across the entire course of the game to execute, there's barely any change at all in the slope of the damage curve. At level 60, there's about a 1200 point difference in DAE. Now, that's significant, but it's very difficult to achieve. Getting this amount of vigor (without the aid of equipment) requires 37 level-ups with the Esper Bismark equipped--or, to put it another way--equipping Bismark immediately upon acquisition in the Magitek Factory and never missing a level in between. It's pretty unlikely. It's also kind of pathetic in comparison to how much finding a better weapon would serve the damage output of a player character. So do stats not matter at all?

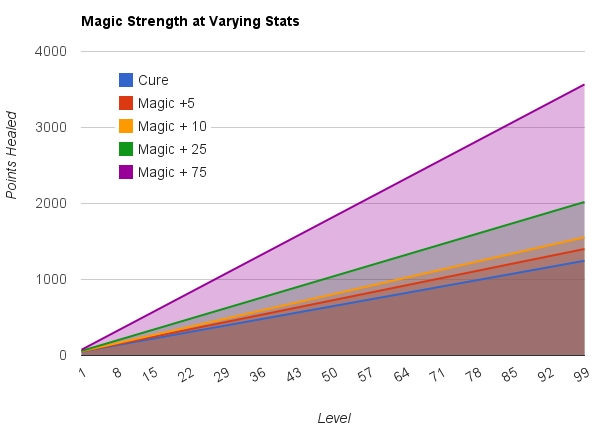

Magic damage shows a very different relationship to its governing stat, magic power. The graph below describes the increasing power of the cure spell as the magic power stat increases.

What's important to notice here is that when you change magic power, the slope of the resulting line--indicating power per level-- changes (a) significantly and (b) immediately. When adjusting magic power, players will see immediate results that really matter. Cure, in particular, sees an important change. At level 55, when it's most necessary, 25 extra points in magic power results in a character outputting around 50,000 more points of healing before emptying their MP pool. That's enough to heal party members from nothing to max about ten times--on top of the base amount of healing at that level. Acquiring 25 additional points of magic power is actually quite easy, requiring only thirteen levels with the Zoneseek or Tritoch Espers. This kind of planning and power-leveling is quite easily achieved in the second half of the game.

At first, it seems strange that only one stat, when modified, makes an obviously meaningful contribution to combat. Yet, I think that this actually holds with the design philosophy as a whole, in that it diminishes the difference between characters. What is the one special ability that every character can use? Magic! Every character is going to learn some amount of magic along the way--there are enough espers for every character to equip one at once. So it makes a lot of sense that magic power would be the most pivotal stat that doesn't rely on gear. Even a character you don't like could be made into a decent fighter if they know Cure and Meteor.

WEAPONS FREE - A LOOK AT LEQ

As noted above, weapons and gear play an enormously important role in determining many of the elements of combat. Indeed, they seem to play a more significant role than any other single factor in the World of Ruin. Weapons and armor used in the final dungeon and against the final boss begin showing up immediately in the WoR, because there are fourteen characters to provide gear for. This has a secondary effect of making it possible for characters with very good gear to take on monsters that are above their level.

This actually shows up in the numbers, when looking at how much DAE a weapon does over the weapon it replaces. The last purchasable sword is the Falchion; no matter how many dungeons the player explores, we know they can buy a Falchion in Maranda, before tackling the last dungeon. Now, let's assume that our player hasn't been using Celes for example, and she's only at level 40. That's not a very good level for going through Kefka's Tower. But what if instead of using the Falchion we equip Celes with the Scimitar? Her DAE goes up about 188 points. That damage is the equivalent of Celes dealing the damage she would output if she were about 2.5 levels higher. Obviously you can't gain half a level, but your weapon can bring you there. If you replace that Falchion with a much better weapon, say, the Ragnarok, you see a much bigger difference: her DAE goes up about 370 points, which is equivalent to gaining five levels of damage. Level 45? That's passable. Slap on an Atlas Armlet accessory for about 20% more damage (for another 5 levels of DAE), and you've got a character whose damage output is functionally that of a level 50 character.

I call this statistic, which measures how many levels a piece of gear is worth, Level Equivalence or LEQ. It's not universally usable; it would fall apart in MMO endgame usage, and a number of other places. But when building a battle system for a single-player RPG, it's a useful way to look at how one piece of gear compares to another. One proviso when using LEQ is that it's very sensitive to the context of levels. In FF6, the higher the starting level of the character using the gear is, the higher the LEQ of the weapon being equipped. I can't predict how this will translate to other games, but my educated guess is that the most meaningful uses of LEQ will come either in a) measurements of the effectiveness of a new weapon, freshly acquired, or b) measuring the performance of characters using certain weapons (or other piece of gear) in situations where that character is succeeding despite being overmatched.

Trying to use LEQ for armor is a little more complicated when it comes to FF6, for several reasons. Foremost among those reasons is that enemy attacks can be physical or magical, and most armor pieces have different stats for each. Another reason is that there are numerous enemy attacks that either ignore armor and deal direct damage, or bypass armor by reducing player character HP by a predetermined fraction. The final reason is that much of the difficulty of the late game is created through hand-touched content in the form of unique monster attacks. Monsters in WoR dungeons above level 40 achieve much of their damage output through the use unique physical attacks that are simply multiples of a "standard" attack. This confounds any systematic approach to knowing what kind of damage to expect from a given enemy. (This is covered in greater depth on the next page.)

Much of the "what armor does for you" will be measured on the next page. But, since we're still here, it's worth noting one more important detail: while heavy armor has an advantage for most of the game, everyone's best set of gear is roughly the same. Of the final purchasable sets, the heavy (crystal) set reduces physical damage by about 59% and magic by just under 40%. The light armor (dark) set reduces physical by 47% and magic by 32%. It pays to be a heavy armor-wearer... but not for very long. The best heavy armor set in the game (Genji armor) provides 70%/65% reduction, but the Snow Muffler (light) set provides 76/52 coverage, with the possibility of nullifying three elements. Similarly, the Behemoth Suit set (which includes a Genji Helm) is almost identical to the Genji set. It's yet another example of the diminution of character classes--especially in the late game.

Trivia! Stamina makes it more likely your characters will evade status debuff attacks... but a ribbon would guarantee it. Speed stats are nice, but Haste 2 is cheaper. Did you know you can control the enemies speed stats through the config menu? It's the "Battle Speed" range; but be careful because it's counterintuitive! 1 = fastest and 6 = slowest.

When buying gear... what are you getting for your money? Because of fantasy-world inflation, you're getting less and less. The first purchasable weapons give you about 1 battle power per 12 gold spent. Not even half a game later, you're paying 30ish gold for one point. By the end, you're paying in the mid eighties for the same one point of battle power! It's even worse with armor. You'll pay about 200 gold for one point of defense (including magic defense) for a Crystal Helm.